The Gold Disc

Armando Iannucci writes about the experience of sitting on the judges panel for the coveted Gramophone Gold Disc Award

I’ve been lucky enough over the past few years to be invited on to various awards panels and flattered enough to accept. Sitting in judgement over a disparate group of other people’s hard work is a peculiar experience; one begins to realise just how artificial the notion of order of merit becomes when you’re trying to compare a biography of a 19th century admiral with a children’s story about elephants, or when you’re asked to quantify the difference between a 10-CD box of Haydn trios and a Vaughan Williams symphony. One might as well try comparing coffee with a wheelbarrow.

The music choice just mentioned was faced by those of us on the penultimate stage of the Gramophone Gold Disc Award, in which a group of us whittled down 10 of the past 30 years’ Record of the Year winners to a set of five to be put before a public vote. Faced with the impossibility of using any scientifically objective method of comparing, say, a Grieg song recital with a Mahler symphony, you find yourself digging deep into intense, personal, unquantifiable consideration of how a performance hits you both intellectually and emotionally. One is forced to consider just what exactly the CD listening experience means, and how each of these pieces alters and magnifies it. As a result, I left feeling that, yes, it’s impossible to come up with some definitive answer as to which is “best” of all time, but that the process of having the contest is still a worthwhile one because the identification and celebration of excellence surely has to have a universally beneficial effect.

The conclusion is a snapshot of where all the trends and pulls of that day’s tastes ultimately settle. It’s fun and illuminating, but never definitive. It’s a serious business, as long as one doesn’t take it seriously.

Listening to Angela Hewitt playing Bach or Paul Lewis playing Beethoven, I’m reminded about how wary we should be about declaring anything to be “definitive”. It used to be that Gould’s Bach and Brendel’s Beethoven were definitive, but as the seasons move on and new generations of pianists come through, we see these older musicians as distinctive rather than definitive: we celebrate the originality of their interpretation but no longer hear it as the last word on the matter. Our judgement is affected by what comes after. Massive orchestras and choruses accompanying Karl Richter’s vision of Bach’s religious masterpieces may have seemed at the time the last word on depicting heavenly paradise, but nowadays it can sound wallowing and muddy, like a choir of angels gathering round a watering hole.

So our judgement is affected by the shifting trade winds of the market and the newest trends in performance. But the reputation of a piece can also affect one’s judgement of how well it was played. The absolutely definitive performance of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony may well have been given a thousand times already, but we’re hardly likely to notice because of the supreme popularity of the piece. We know it so well that the performances that stand out now are more likely to be the ones with a more original twist; playing on period instruments, paring down the orchestra, taking an unusually fast pace. All of these approaches seem more notable because they refresh the piece; they startle us into thinking we’re hearing the symphony as if for the very first time. Blowing away the cobwebs of convention, these performances feel like a recreation of the premiere. They’re not, though: we can never tell what the perfect summation of the score can ever sound like. All we can do is attempt to understand it in as many ways as we can. The recent trend for recording, say, Bach cantatas with one soloist to each choral part throws up interesting and invaluable insights into the structure of the music; as a result, the cantatas sound fresh. But that’s not the same as saying they sound better. What they do, though, is profoundly impact on how we then judge more conventional performances.

Classical music, so often a medium that breathes in superlatives, casually discussing notions of excellence, sublimity, profundity and brilliance, can often appear as if it’s sealed the deal on what is and is not definitive about a performance. And yet its history shows otherwise; the fact that conductors often re-record pieces, that performers like Kennedy can go back to career-defining works like the Elgar Violin Concerto and commit them to CD again because they’ve discovered fresh things to say about them, the fact even that composers conducting their own works can often sound strange and sometimes perverse, or that they’re often compelled years later to go back and revise their works sometimes to the good, often not (there’s a whole thesis in how much damage Bruckner did to his output this way) all tell us that the defining moment, though worth striving for, can never be reached and that to claim otherwise may be to remove music’s final mystery. G

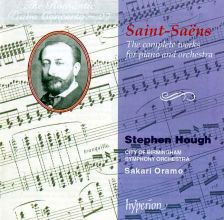

Gold Disc Winner

Saint-Saëns Piano Concertos Nos 1-5

Stephen Hough pf CBSO / Sakari Oramo

Hyperion CDA67331/2

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £8.75 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Full Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £11.00 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.