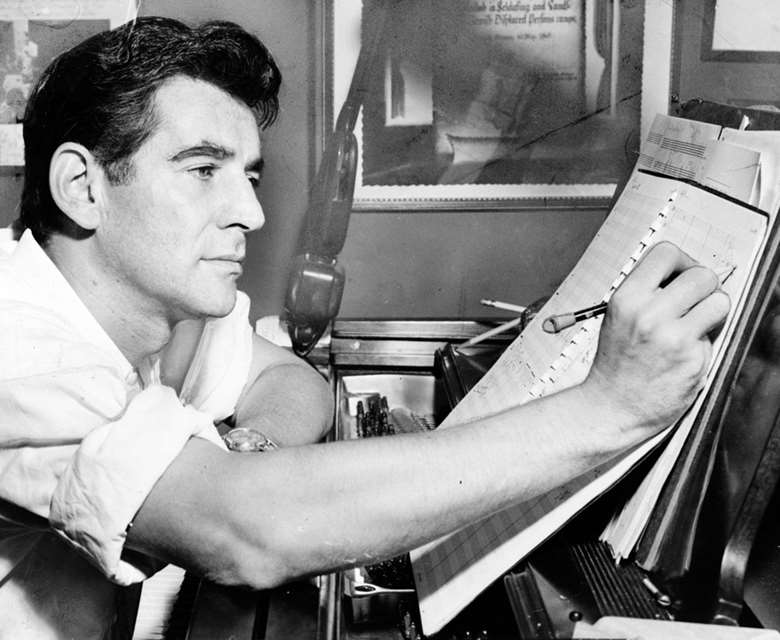

Why Leonard Bernstein's music demands to be danced to

Sarah Kirkup

Wednesday, March 14, 2018

With the centenary celebrations underway, a new Royal Ballet triple-bill devoted to the composer highlights the sheer ‘danceability’ of his music, writes Sarah Kirkup

Dance could have been invented for Leonard Bernstein. As Jerome Robbins, the choreographer and Bernstein’s long-term collaborator, said: ‘The one thing about Lenny’s music which was so tremendously important was that there always was a kinetic motor – there was a power in the rhythms of his work, or the change of rhythms in his work and the orchestration – which had a need for it to be demonstrated by dance.’

Bernstein’s oldest daughter, Jamie, has also alluded to his music’s rhythmic drive, believing that his ‘spectacular sense of rhythm’ is ‘what gives his music a thumbprint’: ‘He synthesised what he got out of Hebrew cantillation with his getting really obsessed with Billie Holiday and Lead Belly in his college years, to say nothing of Stravinsky and Gershwin. Add the Latin-American thread, and he just went bananas.’

Even Bernstein’s ‘podium gyrations’ (as the New Yorker once referred to them) were, in a sense, choreographic: in a review following the opening of the Bernstein-Robbins ballet Fancy Free, which Bernstein also conducted, the dance critic Edwin Denby wrote that ‘his downbeat, delivered against an upward thrust in the torso, has an instantaneous rebound, like that of a tennis ball’.

For Bernstein, music and dance were natural and very obvious partners. During his composing career, he collaborated with Robbins on three major ballets, contributed to several Broadway musicals – most significantly West Side Story in 1957 – and, in 1971, invited Alvin Ailey to choreograph his Mass: A Theatre Piece for Singers, Players and Dancers. Not only that, each of the five movements of his final composition, Dance Suite – premiered by Empire Brass in New York in 1990 – is dedicated to a different choreographer (Robbins, Baryshnikov and Balanchine are all included). This connection between the two art forms can perhaps be traced back to when, as a small boy in Boston, Bernstein had the experience of seeing his first ballet and also hearing the music of Beethoven for the first time (the ballet was set to Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony): ‘Since then’, Bernstein later recalled, ‘I have never heard or conducted this work without some deeply stirring memory of that visual event. I can’t actually recall a single step or choreographic formation; but the general impression remains for me forever attached to the music, so that when I perform the work, something inside me is always dancing.’

As the Bernstein centenary celebrations gather momentum (his 100th birthday would have been on August 25 this year), orchestras, opera houses and musical theatre companies across the world are preparing performances of all things Bernstein – from the movie soundtrack for On the Waterfront to the one-act opera Trouble in Tahiti, plus several of his pieces for dance and musical theatre including Fancy Free and On the Town (both Robbins collaborations). But in one particularly significant event, a dance company – the Royal Ballet, more usually accustomed to tailoring its mixed programmes to specific choreographers – is dedicating its entire forthcoming triple-bill to the composer. And the fact that all three pieces of music were originally conceived as standalone concert works only testifies to the inherent ‘danceability’ of Bernstein’s scores. Opening on March 15, the programme has as its centerpiece Liam Scarlett’s 2014 ballet The Age of Anxiety , set to Bernstein’s Second Symphony bearing the same name. But framing this are two new works by the Royal Ballet’s other two associate choreographers, Wayne McGregor and Christopher Wheeldon. For Yugen, McGregor has been drawn to Bernstein’s choral masterpiece Chichester Psalms; for Corybantic Games, Wheeldon has chosen the violin concerto Serenade. It’s a programme that, believes Wheeldon, reveals Bernstein’s diversity as a composer, with the underlying poetic nature of Chichester Psalms being juxtaposed against the ‘Americanness’ of The Age of Anxiety, and the concluding Serenade representing ‘a combination of the two – it slips between the poetic and a style that’s almost musical theatre, with traces of “Maria” and “Dance at the Gym” from West Side Story’.

Christopher Wheeldon: Serenade

Serenade (after Plato’s ‘Symposium’) for solo violin, harp, percussion and strings was premiered by Isaac Stern in 1954, just three years before West Side Story, and relates to Plato’s dialogue on the nature of love. It is dedicated to the memory of Bernstein’s mentor, Serge Koussevitzky, and remains one of the composer’s most lyrical orchestral works. Wheeldon first choreographed it when he was 22 but hopes that Corybantic Games – featuring Grecian-style costumes by British fashion designer Erdem Moralıoğlu – will serve this ‘extraordinary music’ better this time around. ‘It’s basically a violin concerto in five movements’, he explains, ‘in which Bernstein contrasts soaring, elegiac passages with dynamic, rhythmic sections.’ One obvious example of the latter is the third movement, ‘Eryximachus’, in which the Athenian physician speaks of bodily harmony. For Bernstein’s extremely fast and playful fugato-scherzo, Wheeldon has choreographed a challenging pas de deux , crammed full of intricate steps and executed at high speed.

The violinist Baiba Skride, who recorded the work last year, recently lamented in Gramophone’s ‘Studio Focus’ column the fact that it was rarely performed in Europe. Koen Kessels, the Royal Ballet’s Music Director who is conducting Serenade and Chichester Psalms for the all-Bernstein programme, agrees that it isn’t played as much as it should be and, like Skride, can’t really understand why. ‘Many violinists just don’t have it in their repertoire,’ he says. ‘Perhaps it’s because only the last movement sounds like people expect Bernstein to sound – in other words, like West Side Story. And the first movement, with its opening violin solo – to begin with, you wonder where it’s leading. But it’s a fantastic piece.’

It’s also a piece that perhaps reveals as much about Bernstein as it does about Plato’s Symposium. The musician’s biographer Humphrey Burton has observed that Serenade ‘can be perceived as a portrait of Bernstein himself: grand and noble in the first movement, childlike in the second, boisterous and playful in the third, serenely calm and tender in the fourth, a doom-laden prophet and then a jazzy iconoclast in the finale’.

Wayne McGregor: Chichester Psalms

If Serenade can be described as autobiographical, so, too, can Chichester Psalms. Bernstein had been hit hard by Kennedy’s assassination in 1963 and his anguished Third Symphony, Kaddish, was a direct response to this. Two years later, he harnessed his grief into the life-affirming Chichester Psalms, proof of his determination to reply to violence with the act of ‘making music more intensely, more beautifully, more devotedly than ever before’.

Commissioned by the Dean of Chichester Cathedral, the Very Reverend Walter Hussey, for its 1965 Festival, Chichester Psalms sets six psalms across three movements, to be sung in Hebrew by mixed chorus and, in the second movement, boy treble, accompanied by brass, percussion, harp and strings.

At the time of receiving the commission, Bernstein was in a state of flux. He was on sabbatical from his post as Music Director of the New York Philharmonic and focusing on composition – predominantly ‘12-tone music and even more experimental stuff’, later admitting that ‘it just wasn’t my music; it wasn’t honest’. (As his daughter Jamie has said, if you were a composer in the mid-20th century, ‘either you wrote 12-tone music or you weren’t a “serious” composer’.) But this wasn’t at all what Hussey – an enlightened champion of the arts whose commissions include works by Chagall, Moore, Auden and Britten – had in mind: ‘Many of us would be delighted’, he wrote to Bernstein, ‘if there was a hint of West Side Story about the music.’ And thus, Bernstein was given permission to return to what he knew and loved. ‘It was the most cheerful, tonal music he’d ever written,’ says Kessels. ‘You can almost hear Bernstein saying, “I’ve had six months of serialism, now let’s do something else”.’

Although Chichester Psalms is sung in Hebrew, it draws on vocal part-writing most often associated with Anglican church music, and this combination of Jewish and Christian elements makes a powerful plea for peace in turbulent times. At the same time, its contemporary feel – the ‘bluesy’ treble line, the jazzy lullaby at the end of the piece, the inclusion in the second movement of music cut from West Side Story – means it wears its universal message lightly. For Wayne McGregor, it’s ‘an extraordinarily powerful piece of music’ which spoke to him the first time he heard it – despite the fact that, until now, he has never choreographed a choral work. McGregor also knew instantly that, were he ever to choreograph it, he would want to collaborate on the set design with the ceramicist and writer Edmund de Waal who, as part of a clergy family, had grown up in cathedrals – first Lincoln, then Canterbury – and heard the psalms every day as part of matins and evensong.

One of the first requests de Waal made, after McGregor had approached him with the commission, was to talk to the conductor. ‘He asked me, “Where are you going to put the chorus?”,’ recalls Kessels. ‘All I said was, “This is a choral piece with orchestra, so we can’t put the chorus way back on the stage”, and he said, “Don’t worry, I know this work”. From the start, he had the greatest respect for the music.’

In the event, because of space restrictions, the chorus must sing from the pit, but there is one firm nod to Bernstein’s musical genius: the boy treble will sing from the stage, his uplifting words of Psalm 23 – ‘The Lord is my shepherd’ – contrasting with the tenors and basses singing Psalm 2 – ‘Why do the nations rage’ – from below.

Liam Scarlett: The Age of Anxiety

Man’s capacity for self-destruction and the destruction of others by defying God is at the heart of Psalm 2, and there can be no greater example of this capacity than war – whose very existence was anathema to the pacifist Bernstein. The British poet WH Auden, who had moved to the US in 1939, shared this outlook: he was deeply affected by the Allied bombings of Germany during World War Two and the resulting devastation; and when he joined the Morale Division of the US Strategic Bombing Survey, he learned in horrific detail about the Nazis’ extermination of the Jews. In his epic wartime poem of 1944, The Age of Anxiety, he captured the uneasy atmosphere of war and the issue of conflict, not just between nations but within individuals. When Bernstein read it in the summer of 1947, he found it ‘fascinating and hair-raising’, describing it as ‘one of the most shattering examples of virtuosity in the history of British poetry’. The story of four lonely people meeting in a bar in New York during wartime and the interactions that follow – some real, some imagined – resonated with Bernstein, once described as ‘the loneliest of gregarious men’. He spent the next 18 months compulsively working on the eponymous Second Symphony, which premiered on April 8, 1949, with Bernstein himself playing the virtuosic solo piano part.

Although it wasn’t Bernstein’s intention to adhere strictly to the poem, he ended up doing exactly that: ‘I discovered detail after detail of programmatic relation to the poem – details that had “written themselves”,’ he later reflected. Consequently, in the Prologue of Part One, we meet the four protagonists, each consumed by his or her own thoughts until alcohol and war reports on the radio bring them together; their loneliness is conveyed by a hushed quasi-improvisation by two clarinets – ‘the sound of urban isolation if ever we heard it’ (Gramophone , 11/01). As the discussion of the ‘Seven Ages’ of man commences, prompted by one of the characters buying a round of drinks, Bernstein embarks upon seven variations, each incarnation drawing on material from the previous one. And as the characters embrace a hallucinatory journey into the night – the ‘Seven Stages’ – we hear seven more variations as the four attempt to find their way home. In Part Two, during the shared cab ride – where the characters in Auden’s poem sing a ‘Dirge’ of mourning – the composer employs a 12-tone row, sparking a main theme and then a middle section in which, according to Bernstein’s outline, ‘the self-indulgent aspect of this strangely pompous lamentation’ can be felt. Back at the sole female character’s apartment, the ‘Masque’ begins, the drunken frivolities echoed by Bernstein’s scherzo for piano and percussion, ending in four bars of ‘hectic jazz’. As the party winds down and the characters each find themselves alone once more, Bernstein opts for a more cathartic ending which, as Edward Seckerson wrote in Gramophone, ‘anticipates Marlon Brando’s courageous walk into cinema history at the close of On the Waterfront ’ (3/17).

That ending has been criticised for being overly romantic, but Liam Scarlett – who first came across the piece via West Side Story while he was studying at the Royal Ballet’s White Lodge – thinks it strikes exactly the right balance. ‘The character of Malin makes his final journey on the train looking across towards Manhattan as the morning sunrise begins to show its first rays. He comes to terms with his own faith, his sexuality, and for a fleeting moment there is a breath of hope. That feeling of self-acceptance, no matter how brief, is the most almighty feeling a human can have, and Bernstein captures it perfectly.’

When Scarlett began choreographing his ballet – following in the footsteps of Robbins in 1950 and John Neummeier in 1979 – he ‘entirely immersed’ himself in Auden’s poetry, much as Bernstein did when composing the symphony: ‘When you have inspiration right there in front of you, you have to use it and let it embody and encompass you fully, almost to the point of obsession.’

Scarlett’s work is inevitably the most narrative of the three ballets on the triple-bill, although, like Bernstein – and Auden before him – Scarlett has created characters who can appear elusive. ‘In Auden’s poem, when the characters speak, it’s hard to differentiate between them – maybe this is Auden speaking to us. Bernstein does something similar – it’s his voice we listen to, and the four characters are vessels through which we hear it. I think I’ve done the same with my choreography. The movement language isn’t particularly different from one character to the next, but that doesn’t make the cohesive arc any less strong. In fact, it solidifies the fact that they are all searching for the same thing.’

Conductor Koen Kessels has loved Bernstein’s The Age of Anxiety since he was a student because, he says simply, ‘it has everything’. From the melancholic opening with its echotone clarinets and mystical descending scale to its inventive, evolving variations, and from its toe-tapping jazz-piano scherzo to its lush, filmic climax, this is surely Bernstein at his very best: expert orchestrator, rhythmic genius, and always with a flair for the theatrical. Indeed, as he himself said of his Second Symphony, ‘If the charge of “theatricality” in a symphonic work is a valid one, I am willing to plead guilty. I have a deep suspicion that every work I write, for whatever medium, is really theatre music.’

We’re in no doubt of Bernstein’s theatrical mind being at work across all three of the Royal Ballet pieces; collectively, Serenade, Chichester Psalms and The Age of Anxiety all exhibit – to greater or lesser degrees – elements of his trademark Broadway ‘pizzazz’. But they also reveal an awful lot more about this complex composer, such as his propensity for melody, his talent for innovative orchestration, his love of the human voice and solo instruments, and his attraction to non-musical stimuli (in this case, Plato, the Psalms and Auden). And they also tell us about Bernstein the man: his religious beliefs, his desire for peace and brotherhood, and his conviction that love, not hate, will ultimately prevail.

Even though this music wasn’t expressly written with dance in mind, it seems entirely appropriate that these Royal Ballet choreographers are, for the centenary celebration, tapping into what Sondheim has described as Bernstein’s ‘wonderful sense of theatre’. Collaboration was, after all, what Bernstein – a man who never liked being alone in a room – thrived on. And any collaboration involving dance would surely have made this composer especially happy. Early on in his career, he was warned off composing dance music – ‘such a poor form of music’ – by the conductor Dimitri Mitropoulos. But so great was Bernstein’s passion and respect for the art form that he forged ahead regardless, even when his conducting and composing responsibilities intensified. In late 1943, he wrote to Robbins: ‘I have hardly breathed in the last two weeks … I’m conducting … and my scores pile up mercilessly. My Symphony parts lie uncorrected, and my – our – ballet lives only in the head. But … fear not: somehow I’ll get it done.’