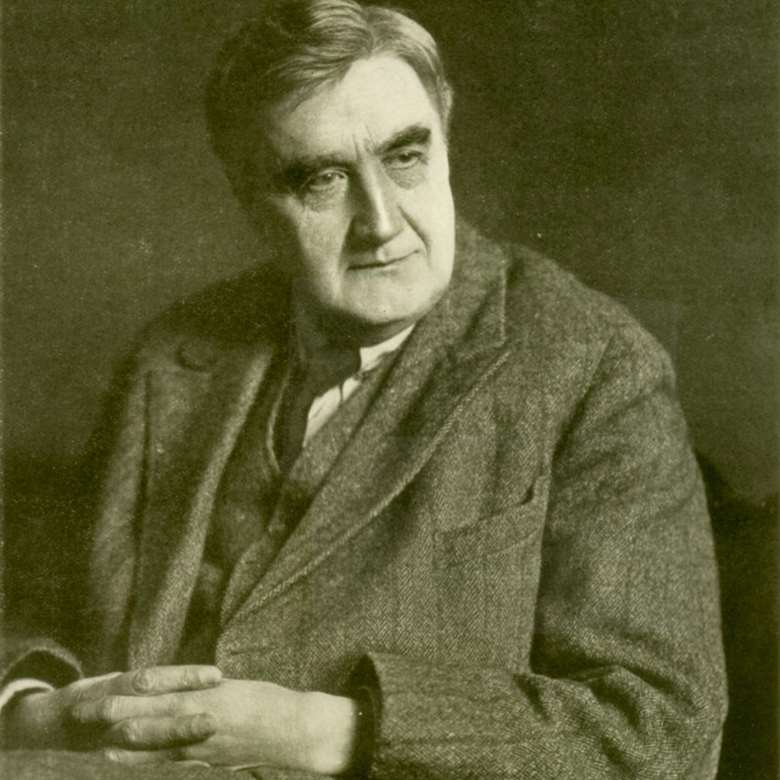

Vaughan Williams’s The Lark Ascending: A Complete Guide To The Best Recordings

David Gutman

Tuesday, May 25, 2021

Vaughan Williams’s hugely popular and ‘quintessentially English’ romance for violin and orchestra has received many outstanding recordings. Here's a complete guide...

There’s no evidence to suggest that the composer himself considered The Lark Ascending in any way exceptional so why has it morphed into the classical hit almost everyone knows? Whereas once this unassuming romance was heard as a direct evocation of the 12 non-consecutive lines by George Meredith which preface the score, today’s wider listenership is largely unaware of its poetic wellspring. The ‘quintessentially English’ tag applicable to the ornate Victorian verse seems increasingly inadequate to explain the music’s global appeal.

In 2011, when New York’s public radio network asked listeners what they’d like to hear on the 10th anniversary of 9/11, The Lark Ascending came second behind Barber’s Adagio. In Australia, possibly helped by its deployment in Anzac-related ceremonials, it currently heads ABC Classic FM’s poll of music that ‘makes your world stand still’. Play the piece to a Frenchman and he may tell you that it sounds like Ravel. What the most celebrated record guide of the 1950s skewered as the aesthetic vulnerability of Vaughan Williams’s legacy (‘a steady trickle of pentatonic wish-wash’) looks set to win The Lark Ascending an army of new friends in the Far East. Put crudely, they think it sounds Chinese.

Is this great music?

The composer’s estate pours the proceeds into musical good works. And yet, critically speaking, The Lark Ascending isn’t taken seriously. Cynics and those in thrall to the Germanic model of what constitutes great music insist that the piece owes its ubiquity to the fact that it’s just the right length for a passive reverie between domestic chores, that nothing actually happens in it, that its sensibility is innately conservative and rural. Much of this is factually incorrect but can’t be comprehensively refuted here.

Vaughan Williams was no escapist. That he belongs in the left-leaning internationalist company of Copland and Shostakovich is attested by the conscientiously acquired earth-rootedness of his mature idiom and its determination to articulate shared feelings, particularly in time of war. At the same time, his best music succeeds by seeming purer (more Sibelian?) than theirs. As The Times noted after The Lark Ascending’s first orchestral outing, in June 1921, it ‘showed serene disregard of the fashions of today or yesterday. It dreams its way along.’ Ursula Vaughan Williams maintained that her husband, a reluctant countryman, could never have identified an actual lark, and many stories (not least her own) about the work’s genesis have been shown to be apocryphal. What we do know is that he began writing it before the First World War and completed it only after his life-changing experiences as a stretcher-bearer at the front. The ambiguities are all the greater because, like most creative Britons of his time and class, Vaughan Williams felt it necessary to appear more amateurish than he was. The Lark Ascending may be thought ‘slight’ but it is motivically integrated, deftly orchestrated and loved by millions.

So is this straightforward nostalgia or did the composer hard-wire something else into the piece from the start? Take his notation of the surprisingly tricky opening: those open chords move in parallel across the bar-line, creating an impression of ‘otherness’ through their distinctive modal harmony. Recordings demonstrate how these have slowed over the years as the music’s quality of repose has seemed at once more precious and more unattainable in a commodified, switched-on world. It sounds preposterous to claim that the piece might be conceived in terms of a dialogue between representation and commentary, but in creating that potent sense of loss Vaughan Williams must be doing something more than contrasting whimsical bird music with a folksier ground-level middle section. Performances aspiring to seamlessness, in which you might not guess that the cadenza-like passages are unbarred, have begun losing ground to those which embrace the discontinuities. Meaning is always in flux, as with the Adagietto of Mahler’s Fifth Symphony, which within a decade went from a celebration of earthly love to a funeral favourite. Music has this mysterious ability to mean what we want it to mean, to acquire a life of its own. All of which renders questions of authenticity more than usually problematic.

Early and ‘Period’ recordings

There are in fact two ‘period’ performances of The Lark Ascending, one dating from 1928, not long after the work was premiered by its dedicatee, Marie Hall, but featuring a different violinist. The other is a 1990s project embodying the neatly sanitising mindset of that time. The composer himself directed it at the Three Choirs Festival as late as 1956, before ‘authentic’ meant something else. Isolde Menges, sister of maestro Herbert Menges, is the soloist in that early 78rpm set (HMV; freely accessible via the AHRC Research Centre for the History and Analysis of Recorded Music at charm.kcl.ac.uk), a fascinating document in which she plays with confidence, continuous well-controlled vibrato and a very straight bat. The accompanying instrumentalists under the young Malcolm Sargent seem less interested in precise attack, with even the strings’ use of portamento reflecting inadequate preparation as much as stylistic intentionality. As there’s none of the topping and tailing customary when 78s are tidied into more modern commercial formats, we are reminded that chords were routinely prolonged in the run-up to side breaks. The generally brisk speeds, extending to a businesslike closing cadenza, might just have been determined by the need to shoehorn the music into manageable chunks; Stanford’s ‘Leprechaun’s Dance’ (Op 79 No 3) occupied the fourth side. No such considerations affected Barry Wordsworth and the New Queen’s Hall Orchestra in 1992. More numerous gut strings back soloist Hagai Shaham (consistently sweet, if somewhat bland) while ceding pride of place to woodwind instruments, sonically attractive and literally woody. Yet the heart does not soar. The big orchestral return at figure 33 feels perfunctory and the sound is too dense.

Back – or forward – to the 1940s! The late Michael Kennedy always spoke highly of the Boyd Neel Orchestra’s 78s with soloist Frederick Grinke (Decca, 6/40), but neither that recording nor Sargent’s Columbia 1947 remake with David Wise (Dutton, 5/95) can be readily obtained today. The earliest version to survive is the 1952 Parlophone 10-inch LP made by Sir Adrian Boult and the LPO with the band’s sometime leader Jean Pougnet. This is of interest to Beatles mavens as one of George Martin’s early classical projects, but its high reputation among Vaughan Williams fanciers is a little mystifying. The conception is taut and to the point, but the soloist has one of those rapid, intense vibratos that, for me at least, fails to transcend its period.

The Lark Ascending, rather suited to an era of shorter playing times, found itself thereafter confined to the margins on 12-inch LP – a bit player in some English music assortment or a makeweight for a symphony. Only much later did it start headlining soloist-led collections, ultimately enlisted as a marketing tool for CD anthologies in which it plays a relatively minor part. With today’s online platforms, the wheel has turned full circle – but that is to get ahead of ourselves.

Accusations of parochialism

Vaughan Williams may have believed passionately that classical music was the birthright of everyone, but he would have rejected the lazy parochialism censured inGramophone’s review of the first American recording of his piece, in which George Szell’s assistant Louis Lane directed Rafael Druian and the Cleveland Sinfonietta (Columbia, 10/64; reissue, 3/81 – nla): ‘I have a feeling that the very “authenticity” of many English performances, the “dew-on-the-grass” effect, lies more than anything in their very tentativeness musically, just as the celebrated Viennese “lilt” is often the result of slack discipline and no more. Give me polish and confidence like this.’ You may be surprised to learn that those are the words of the late Edward Greenfield in younger, less emollient days. And sure enough, there has been a tendency to overlook the technical shortcomings of indigenous practitioners while berating Johnny Foreigner for failings real or imagined.

No special pleading is required for Hugh Bean, an orchestra leader who, when not keeping Otto Klemperer’s show on the road, was a distinguished concerto soloist and teacher. It’s difficult to listen to his familiar rendition with fresh ears, and I found his direct lyrical warmth as appealing as ever. Boult conducts with absolute naturalness, too, so every gear change glides by without strain. If there is a downside it’s apparent from the very start. Boult, prioritising that sense of line over the composer’s dynamic gradations, makes little of the ppp marking attached to all but the muted horns. Bathed in golden-age analogue stereo from HMV’s Abbey Road the music-making doesn’t set out to ruffle feathers, but then why should it?

Sir Neville Marriner and Iona Brown offer something radical with their first recording. The music is given more space, partly a matter of broader tempos but also of microphone placement in the old Kingsway Hall in London. The ASMF’s jewel-like sonority is located in a resonant space, the soloist’s silvery presence seeming to come from above and behind. The cooler, more objective quality of the reading appears to reflect some lines from the poem that Vaughan Williams does not quote directly in the score: ‘The song seraphically free / Of taint of personality, / So pure that it salutes the suns’. Confusingly, this is not the version chosen for inclusion in Decca’s recent 28-disc tribute, ‘Neville Marriner: The Argo Years’, which gives us the same performers’ ASV remake. Brown, still excellent, is more closely observed, the horns too forward. Perhaps the presence of underground-train rumble and some digitally acquired glare up top persuaded the compilers to pass over the genuine article.

Pinchas Zukerman, who recently re-recorded The Lark Ascending with the RPO, was long the biggest celebrity associated with it. He joined the sessions as a favour to his friend Daniel Barenboim, and his contribution has the strengths and weaknesses to be expected of a recording made virtually without preparation. That gorgeous tone survives close microphone scrutiny, but generalised romantic warmth replaces any real sense of other-worldliness, and the sometimes brusque accompaniment from the ECO does not live up to a sensitive opening. Greenfield was positive, though: ‘This is the lark singing in the heat of day.’

A bunch with flaws

It would be some years before a player of comparable individuality engaged with the piece in the recording studio. Vernon Handley’s LPO account, steeped in the Boult tradition, finds David Nolan a tad oversweet. Having coped with the austerity of Paavo Berglund (HMV, 2/81 – nla), RPO leader Barry Griffiths is not inspired to his best form by the soft-focus passivity of André Previn. Michael Davis fares better with his old orchestra, assuming that the insistent vibrato isn’t distracting. Bernard Haitink and the LPO bring in teenage sensation Sarah Chang for a relatively fast-paced rendering in which Chang is wonderfully secure but fundamentally miscast: the timbre too beefy, the vibrato too wide. Better this, however, than the insecurity of Michael Bochmann, coping with an ensemble on the cusp of disintegration. Two recent recordings intended to sit within thematic programmes go better. Lyn Fletcher, leading Sir Mark Elder’s Hallé, is notably cool and collected on an ‘English Landscapes’ album exceptionally well recorded by Andrew Keener and Simon Eadon. James Clark does the honours for ‘Made in Britain’, a John Wilson project with the RLPO that perversely elects to torpedo the idyll with Edward German’s Nell Gwyn overture.

Readers may be expecting me to top-rate Tasmin Little, whose first recording was made in the presence of the composer’s widow and whose remake boasts perhaps the most beautiful sound. Sir Andrew Davis is not prone to expressive exaggeration, and if he has slowed down just a little over the years so too did Boult. Little is among the most delicately responsive of all, carefully inflecting the line to convey both sadness and rapture. However, her intonation is not always absolutely spot on.

Left-field tendencies

Nigel Kennedy’s recording, for all its unapologetic self-indulgence, stopped me in my tracks. This is supremely accomplished playing in a way that Little’s, alas, is not. Sir Simon Rattle’s old Birmingham band is captured with what was then unprecedented depth and fidelity in its new hall. Forget Kennedy’s self-penned booklet-notes, which are a typical mix of insight and silliness. There’s plenty to marvel at even if the interpretation is a bit bonkers too, replete with expressive overstatement from all parties and grinding to a halt more than once over an unprecedented 17'30".

While The Lark Ascending is not an obvious candidate for live recording, Richard Tognetti (with Roland Peelman) leads the Australian Chamber Orchestra a merry dance, marking a yet more complete rupture with the polite way of doing things. Tognetti’s line, peppered with constant inflections of pitch and timbre, is presumably meant to sound as if he’s making it up as he goes along. Not always perfectly in tune, he probably doesn’t care, his vibrato coming and going with complete freedom and in the most unexpected places. If you find this difficult to listen to there’s a rival concert version from down under featuring Michael Dauth under the direction of Mark Wigglesworth, never one to gild the lily. While they pace the outer sections slowly and avoid celebrity glitz, there’s little in the way of mystical transcendence. Or was it just that I was distracted by extraneous audience noise?

Most controversial, in the UK at least, has been the studio recording by Hilary Hahn with Sir Colin Davis and the LSO, which, like Kennedy’s, pairs the work with Elgar’s concerto. The disc received a mere two stars from The Guardian and excited scant enthusiasm here. A puzzle. Hahn’s detached and analytical style is scarcely an unknown quantity and might have been made for this music. Yes, her vibrato is slower and wider than might be anticipated, the timbre not without a certain sinewy quality. Still, every note is a miracle of fine tuning, clean articulation and impeccable control. This is a Lark with backbone. Under Davis – who cannot, of course, be prevented from singing along – the LSO turns in what seems to me the most remarkable realisation on any of these discs. The opening gestures are too slow to fulfil their structural function but the playing could scarcely be more rapt. The bigger hesitations towards the end at least take their cue from the commas marked in the score. The high-end recording, which might not agree with some sound systems, works a treat on mine. The score turns out to have been in Hahn’s life from early childhood, having been one of her mother’s favourites.

Star vehicle

In the last 10 years The Lark Ascending has become an accepted star vehicle. Janine Jansen, a virtuoso who champions the piece in concert, seems less involved on her debut album for Decca. Nicola Benedetti, whose playing is never less than finely calculated, has a more forceful collaborator in Andrew Litton; they give themselves more space without necessarily plumbing any deeper. Both are preferable to Julia Fischer, whose ‘Poème’ miscellany was respectfully received in the wake of the death of its conductor, Yakov Kreizberg. Sadly, their interpretation proves drab, and that final infinite upward spiral needed more practice. Two recent home-grown contenders have more to say about the music. Tamsin Waley-Cohen doesn’t have Hahn’s impregnability yet manages a lingering, questioning reading, rendered uncompetitive only by her inelegant accompanists. Better in this respect is the self-conducted Thomas Gould version captured live in Riga. While Gould can take to the air with the best of them, he brings out the distinct qualities of human and avian aspiration in a way Boult might have found unidiomatic. The other work is Beethoven’s concerto, a pairing never contemplated in the 20th century.

What, then, are we looking for today as the storm clouds move ever closer? What price gentleness, civility, grace and that particular ‘English’ quality of repose without a truly watertight technique? My No 1 is an unfussy old-school rendition but I am conscious that younger listeners may prefer the more active and malleable interpretations of recent years. A different shortlist might be assembled, still haunting but perhaps less score-bound, with the likes of Gould leading the way. I am struck too by how much depends on one’s personal response to the timbre and intonation of individual players and their presence in the mix. Too flamboyant or forward a placement and the composer’s romance becomes a concerto – albatross rather than lark. That cannot be right whether the soloist is an established star or a team player par excellence. This survey has barely scratched the surface of the recent explosion of recordings (you can even hear the violin and piano version courtesy of Matthew Trusler and Iain Burnside – Albion, A/14), but there should be enough diversity to satisfy the most insatiable fan.

Recommended Recordings

The Purist's Choice

Iona Brown / Marriner

(Argo)

Not the most ingratiating interpretation, nor the best-preserved sonically, but nowhere else does the Lark soar more convincingly, finally unfettered by earthly concerns.

The Mould Breaker

Nigel Kennedy / Rattle

(EMI / Warner Classics)

The Lark Ascending on the grandest scale, pregnant with new possibilities – technical, interpretative and otherwise. This is a special event rather than a safe library choice.

The Dark Horse

Hilary Hahn / C Davis

(DG)

A controversial rendition of this popular piece, setting an implacable protagonist with flawless intonation against a lovingly personalised orchestral backdrop.

The Top Choice

Hugh Bean / Boult

(EMI / Warner Classics)

Warm-toned and sensitively recorded, this reassuring mainstream option, under the work’s original conductor, still sounds well enough to warrant the prime recommendation.

Selected Discography

Date / Artists / Record company (review date)

1952 Pougnet; LPO / Boult

Dutton CDBP9703 (10/53R, 12/00); EMI 903567-2; LPO LPO0097

1967 Bean; New Philh Orch / Boult

EMI 207992-2; 764022-2 (10/67R, 1/01R)

1972 Brown; ASMF / Marriner

Argo 414 595-2ZH; Decca 452 707-2DF2; 460 357-2DF2; 478 5692DB; Eloquence ELQ442 8341 (10/72R)

1973 Zukerman; ECO / Barenboim

DG 439 529-2GGA; Eloquence ELQ442 8333 (4/75R)

1982 Brown; ASMF / Marriner

ASV PLT8520; CDDCA518; Decca (28 discs) 478 6883DH28 (5/83R)

1985 Nolan; LPO / Handley

CfP 574880-2 (12/85R, 10/87R, A/01); EMI 678271-2; 098202-2

1986 Griffiths; RPO / Previn

Telarc 2CD80738; CD80138 (7/87R)

1987 Davis; LSO / Thomson

Chandos CHAN9775 (1/88R)

1989 Bochmann; English SO / Boughton

Nimbus NI5208 (2/90); NI7013; NI7009; NI1754; NI5210

1990 Little; BBC SO / A Davis

Apex 0927 49584-2 (8/91R); Teldec 2564 69848-3 (5/03)

1992 H Shaham; New Queen’s Hall Orch / Wordsworth

Argo 440 116-2ZH (5/94)

1994 Chang; LPO / Haitink

EMI 627910-2; S 585151-2 (12/95R); Warner 984759-2

1997 Kennedy; CBSO / Rattle

EMI 631514-2; 557411-2; 697588-2 (1/98R)

2002 Tognetti; Australian CO / Peelman

ABC 476 102-6

2003 Hahn; LSO / C Davis

DG 474 8732GSA; 474 5042GH (11/04)

2003 Jansen; RPO / Wordsworth

Decca 475 0112DH (11/03)

2005 Fletcher; Hallé Orch / Elder

Hallé CDHLL7512 (12/06); CDHLD7532

2007 Benedetti; LPO / Litton

Decca 478 6106DHUK; 478 5338DHINTL (A/09R)

2009 Dauth; Sydney SO / M Wigglesworth

Melba MR301131 (6/12)

2010 J Fischer; Monte Carlo PO / Kreizberg

Decca 478 2684DH (8/11)

2011 Clark; RLPO / Wilson

Avie AV2194 (12/11)

2013 Little; BBC PO / A Davis

Chandos CHAN10796 (1/14)

2014 Gould; Riga Sinfonietta

Edition EDN1058 (7/15)

2014 Waley-Cohen; Orch of the Swan / Curtis

Signum SIGCD399 (1/15)

This article originally appeared in the 2015 Awards issue of Gramophone. Subscribe to Gramophone