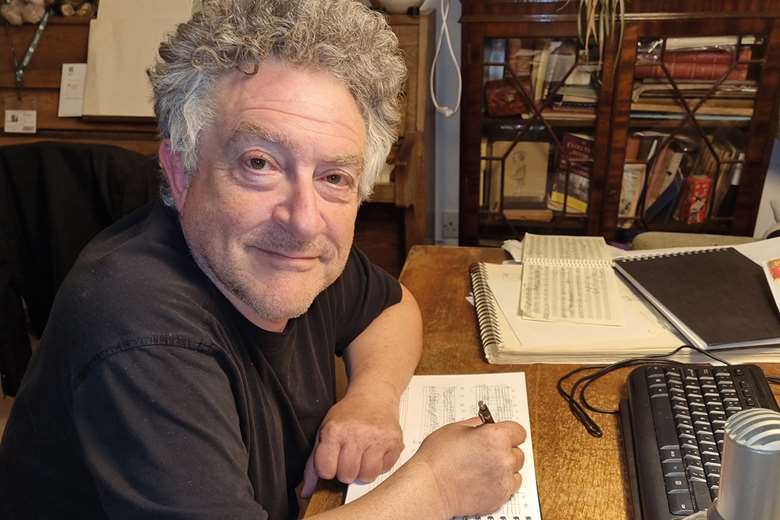

Robert Saxton: Contemporary Composer

Richard Whitehouse

Friday, July 12, 2024

Richard Whitehouse explores the vast and varied output of a versatile, inventive and ultimately fearless British composer

Over a career of more than five decades, Robert Saxton has amassed a body of work whose expressive scope and formal diversity are underpinned by a technical consistency to make its overall evolution the more fascinating. Whether or not the experience of his recent works is evident in the assurance of his earliest acknowledged pieces (or, indeed, vice versa), Saxton remains unafraid to tackle weighty and demanding subjects in the knowledge that continuity across time, and between eras, is the surest means by which creative artists leave their mark.

His works retained from the 1970s confirm Saxton’s awareness of and inventive response to European modernism. Hence the methodical if never predictable trajectory of the solo piano work Ritornelli and Intermezzi (1972), and the distinctive response to WH Auden in What Does the Song Hope For? (1974) for soprano and ensemble, which was the first piece to bring him international acclaim. The Piano Sonata (1981) was a centenary tribute to Bartók, its unforced and resourceful tonal follow-through duly becoming a hallmark of Saxton’s approach in his 1980s orchestral and ensemble pieces.

In Scenes from the Epic of Gilgamesh – a work that is subtle yet approachable in its idiom – Saxton reveals an understated orchestral mastery

Major works from this period include The Ring of Eternity (1982-83) for orchestra, with its evocative response to metaphysical poetry, The Sentinel of the Rainbow (1984) for small ensemble, with its variegated rendering of Teutonic mythology, and Concerto for Orchestra (1984), with its abstract while never detached take on Jewish mystical writing expressed through iridescent textures whose virtuosity gained the admiration of Elliott Carter. This approach to composing further evolved in Circles of Light (1984-85), which takes its cue from Dante in a ‘chamber symphony’ of audibly imaginative subtlety, followed by In the Beginning (1987) for large orchestra, with its pointedly equivocal response to concepts (biblical or otherwise) of growth and rebirth. (The first four of these works were recorded by Oliver Knussen for EMI, 4/90 – an album that urgently warrants reissue.) Concertos then became a focus: those for viola (1986), violin (1989) and cello (1992) all reassess generic archetypes, and that for trumpet, Psalm – A Song of Ascents (1992; recorded by Simon Desbruslais for Signum, 2/15), has been hailed by conductor Kenneth Woods as ‘music that could only come from an extraordinary creative personality’.

The climax of this period, Caritas (composed 1990-91) is an 80-minute opera to a libretto by Arnold Wesker concerning the fraught interplay of personal and societal crises during the Peasants’ Revolt. Its second act, a single scene with the ‘heroine’ immured as an anchoress and rapidly succumbing to insanity, is a harrowing high point of post-war British opera: not least because it makes the distinction between an unquestioned acceptance of dogma and a rational outlook enabled by reason, something whose relevance has not faded over time and that has rarely been of more crucial importance than it is now.

Several chamber works in Caritas’s wake imply changing priorities if not lesser ambition. Contrasts intonational and temporal underpin the skewed classicism of the piano quintet A Yardstick to the Stars (1995; recorded by the Brunel Ensemble for NMC, 6/00); while two string quartets – the animated Fantazia (1993; on the same disc as the above) and the extended formal and expressive interplay of Songs, Dances and Ellipses (1997; recorded by the Kreutzer Quartet for Métier) – find the composer absorbed in primarily abstract if never abstruse concerns.

Concurrently, Saxton was rethinking his approach to composition and his musical idiom in particular. Something of this is evident in the cantata Canticum luminis (1994), which sets texts by Lucretius and Isaac Newton for chorus and soprano and was written for his soprano wife, Teresa Cahill, with whom he has enjoyed a creative relationship of some 45 years. It is even more directly evident in Five Motets (2003; recorded by The Clerks and Edward Wickham for Signum, 1/10), whose settings both of biblical texts and of Saxton’s own poems address the ever topical issue of ‘wandering’ as a corollary to that of tonal evolution. As he himself has described it (in correspondence for this article), ‘Tonality is, for me, the relationship between detail and the large(r) scale so that everything “functions” as part of the whole. Having nearly always embraced pitch centres as focal points, during the past 25 years I have worked with modal scales, employed as sets in conjunction with underlying long-range tonal or harmonic planning.’ Thus, his music’s ends have gradually become more overtly tonal as its means have become more intrinsically serial.

The defining work in this respect is Saxton’s second opera, The Wandering Jew (completed 2010), the long gestation period of which is hardly surprising given its scope and ambition (he first thought of writing it more than 20 years before it was completed). In eight continuous scenes (to the composer’s own libretto) linked by largely orchestral interludes, it follows its ostensible anti-hero during his journey from the sacking of Jerusalem to the aftermath of the Holocaust. These scenes proceed via a sequence of descending fifths away from then back to the ‘A’ on which the opera opens and closes – or rather, returns to its beginning. The music is rhythmically and harmonically lucid, its textures complex though euphonious as to place philosophical above theatrical concerns. It further reaffirms the possibility of deploying tonal procedures without recourse to those fashionable ‘siren calls’ of stylistic pastiche and meritocratic accessibility.

The steady flow of major works testifies to its enabling effect on Saxton’s musical language. This comes through the Third and Fourth String Quartets (2009-11 and 2018, recorded by the Kreutzer Quartet for future release on Métier), in which modernist precedent has assumed unexpected if logical turns; or the characterful trumpet concerto Shakespeare Scenes (2013; on Desbruslais’s album). More introspective is the song-cycle for baritone and piano Time and the Seasons (2007-12), in which memories of his lifelong attraction to the south-eastern Norfolk coast elide with the seasonal traversal from and back to winter. Circular procedures also inform the oboe concerto A Hymn to the Thames (2020; on a Divine Art ‘Portrait’ album, along with the song-cycle), which follows that river’s journey from its Cotswolds source to its ultimate destination, a North Sea estuary – soloist leading orchestra on to a climactic arrival and, in turn, a comparable renewal.

The piano anthology Hortus musicae is inspired by a ‘musical garden’ with all its allegorical and metaphysical implications. The five pieces of Book 1 (2013) embody this in ingenious ways, not least the ear-catching floral clock of ‘Hortus temporis’ or the alluring synthesis of precision and elegance in ‘Hortus infinitatis’. The seven pieces of Book 2 (2016) include Saxton’s invoking of fondly remembered music in ‘Beech Bank (À la recherche) …’; and ‘Hortus animae alis fugacis’, whose deft play on meanings closes this circular tonal trajectory.

Saxton was evidently reluctant to call Scenes from the Epic of Gilgamesh (2022) a symphony, yet this musical recreation of one of the world’s oldest written texts has real formal cohesion and expressive unity – its closing ‘Apotheosis’ opening out the melodic potential of earlier ideas on the way to a powerful culmination with the hero forced to seek immortality by other means. In a work that is subtle yet approachable in its idiom, Saxton reveals an understated orchestral mastery that one would hope he might pursue in further such pieces – whether or not ‘symphonic’ in conception.

In progress is a major organ cycle for Jonathan Clinch using Hauptwerk software in an online recording project (see jclinch.com), the organ recently having had a crucial role to play in Saxton’s eloquent memorials to colleagues John McCabe, Oliver Knussen and Harrison Birtwistle. Yet as is confirmed by his solo violin sonata Reflections in Time (2023) with its gripping take on the Bach–Bartók lineage, Saxton remains unafraid to fuse achievements from the past with possibilities for the future.

This article originally appeared in the August 2024 issue of Gramophone. Never miss an issue of the world's leading classical music magazine – subscribe to Gramophone today