Meeting Jonathan Tetelman – a tenor for our times

Martin Cullingford

Friday, March 21, 2025

Midway through a week recording Tosca in Rome for DG, Jonathan Tetelman takes time out to tell Martin Cullingford about the experience, his past, his plans – and why recordings are so important

The sleek Renzo Piano modernity and warm cherry-red wood of the Sala Santa Cecilia may feel far from the finery and filigree of a traditional opera house; it certainly feels far from the medieval bulk of Castel Sant’Angelo, which squats by the Tiber and from whose battlements Tosca’s tragic heroine hurls herself. But then, Rome has always been a succession of styles, centuries of serendipity having shaped its soul just as much as formally planned piazzas and palazzos. And after all, so many monuments of ancient Rome were about theatre – about the telling of tales and the staging of spectacles both heroic and horrific. An auditorium that opened at the turn of the 21st century hosting an opera premiered at the turn of the 20th and set at the turn of the 19th somehow fits right in with Rome’s embrace of the passing of historical periods. And, of course, what a concert hall of this nature also offers is excellent acoustics – which is particularly important when the performance is being recorded.

Deutsche Grammophon is recording Tosca, featuring its star Puccini tenor of today, Jonathan Tetelman, as Cavaradossi, with Eleonora Buratto in the title-role and Ludovic Tézier as Scarpia. In many ways, the format is a perfect union – not a compromise, that implies too many negatives – of a studio session and a live production, being recorded over three public concert performances in late October 2024 (Tézier was indisposed on the night I attended, but sang in the other two concerts). Attending an opera in concert, while clearly not how the composer intended it to be heard, can bring rewards – not least through the visually vivid focus brought to the orchestral score, in this case played by the Accademia di Santa Cecilia Orchestra, sitting centre stage behind the line-up of mics awaiting the arrival of Puccini’s protagonists.

‘I want to do things that allow me to be artistic. It’s not about the role; it’s about what I can bring to the role’

For this performance, the soloists are spared the requirement to act, yet, paradoxically, this imposes on them additional challenges. During sections between singing they can’t fill time with movement or interaction; they have to stand still, never straying far from the mics, and yet they must respond to the music, being required to reflect their character’s internal emotional journey through facial expressions. And when they do sing, absolutely everything has to be conveyed in the voice. It’s an observation I put to Tetelman the following morning, when we meet at a trendy terrace bar high above the city’s east side, from which we try (and fail) to locate Castel Sant’Angelo.

‘I’m really concentrating,’ he confirms, with a welcome warmth and energy despite the late finish of the previous night’s post-show socialising. ‘I mean, in these performances I’m not necessarily trying to convey the entire arc of the story. It’s not really possible, because I don’t have the props, I don’t have the set. I’m more trying to find the emotion in just the voice.’ That, I can confirm, he indeed did superbly (listeners can judge for themselves, as the recording’s release is imminent). But is there also a danger that, shorn of physical immersion in the drama, it can feel episodic? ‘I mean, it’s a little difficult to kind of piece it all together,’ he accepts. ‘So I’m really trying to be attentive to what the orchestra is doing, and trying to connect to that.’

Tosca dream team: soloists Tetelman, Buratto and Tézier take a bow at Rome’s Sala Santa Cecilia at one of the recorded concert performances in October 2024 (photography: Musacchio, Pasqualini - MUSA)

For members of the public not given regular access to recording sessions, it’s probably the closest they get to being at one; and as far as Tetelman is concerned, that’s actually what they’re witnessing. ‘I’m not really thinking of this as an operatic performance, I’m kind of thinking of it more as a recording.’ Of yesterday’s performance, he tells me, ‘My focus was really on the Act 1 duet. And then “Vittoria!” – I wanted to have a good take of that. And the third act, I wanted to have complete – a very emotional, very sincere, third act. And I think I got most of the stuff that I was looking for. It’s strange to kind of “piece out” the opera like this,’ he admits; but channelling his focus where he thinks it’s most needed is, he adds, ‘a better use of my time and energy’.

There’s certainly nothing remotely static about the recording – instead, it has a powerful sense of drama that belies the black-tie, ball-gown concert get-up of the evening, and in its moments of repose, it has a real sense of beauty that reflects an exquisite attention to detail. The benefits of a multi-evening concert performance means those involved can analyse it day by day, and listening intently on headphones can reveal forensic details: ‘You don’t notice it when you’re listening in a hall because the voice is resonating all around, but through headphones you can really hear these tiny little things that the microphone picks up. It’s very clinical. But to bring emotion and also to think of your voice clinically is tough.’ When recording, he continues, ‘Everything is under a microscope – a hundred times more. You only have the music to tell the story, and it’s not just based on beautiful sounds, either; it’s also about finding this emotion. I think Puccini is one of the harder composers to record.’

A staged production would have a director with a particular dramatic vision, so I wonder, in the case of this concert performance, how much guidance – or, indeed, how much freedom – there was on this front. ‘I’m definitely free to do what I want because we don’t have a director. But as with writers who find that the more freedom they have, the more difficult it is to write something down, I find it a bit challenging because there’s not that structure of a staged production. The first performance versus the second was kind of a learning curve for me.’

Best of both worlds

Tetelman’s Tosca – or his Cavaradossi contribution – now joins an extraordinary list of iconic recordings of the work. And when we cite and celebrate tenor stars of yesteryear, Cavaradossi so often serves as touchstone for their talents. ‘I’ve listened to quite a few recordings, not only studio recordings but also some live recordings, and I just find it fascinating to see how different the interpretations can be,’ he says. ‘It’s the same music – so it really comes down to what somebody can do, and wants to do, with that music. And with the live recordings you get this heightened feeling that you don’t necessarily get with the studio stuff. I mean, the studio stuff is beautiful, but in live recordings you can feel this energy that’s not in the studio. I think that having this opportunity with an audience means we’re going to get that live feel – but in a studio-type setting.’

The conductor of this best-of-both-worlds scenario is Daniel Harding, newly appointed Music Director of the Orchestra and Chorus of the Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia. As it happens, this is Tetelman and Harding’s first musical meeting. It is also Harding’s first Tosca. So new beginnings on so many levels. ‘Wow! I mean, he’s a force of nature,’ Tetelman enthuses. ‘His energy is unmatchable, and last night I really felt so connected to his breathing and his gesture and his delivery with the orchestra.’

Tosca represents a series of ‘firsts’ for both Tetelman and conductor Daniel Harding (photography: Musacchio, Pasqualini - MUSA)

For Tetelman, the Tosca recording follows an album exploring Puccini’s wider operatic work which won a 2024 Gramophone Award. That, however, followed a DG debut that barely touches the composer’s music. ‘Actually, the Puccini album was the first album idea,’ he says, ‘but we held off on it because of the upcoming centenary of his death.’ With plenty of time to plan, then, Tetelman could shape a Puccini album that is not, as he puts it, ‘run of the mill’, a ‘best of’ Puccini, but is rather one that delves into some lesser-known works. It also meant he could showcase valued colleagues through collaborations. ‘I have a lot of young artists I want to promote because I think they’re great. And I wanted to include ensembles because I think Puccini is not just about the arias. I think his ensemble writing is excellent. And to feature a couple of duets, a trio and a quartet on the album made it more of a discography of Puccini rather than a discography of me.’

Gramophone has been far from alone in identifying Tetelman and the music of Puccini as a fine fit. But does he, as singer, feel the same? ‘Yes, completely. I also think that a lot of my technique is built on who is writing. I really resonated with the way Puccini writes, and I knew when I started singing Puccini that I would eventually become a Puccini tenor. But before that, I never felt that that was possible. It wasn’t that I embody this Puccini-ness, it’s just that it kind of chose me. I feel like I can connect to this music very well. And my voice connects with it without any manipulation.’

Tosca was premiered in 1900. Does Tetelman see the opera as belonging to the end of the 19th century, or does he regard it as being a work of the beginning of the 20th? ‘You know, it’s hard to answer that question. I think it has kind of a place in both. And that makes it more or less a perfect opera – it has such timelessness. You can set it in the way that Puccini set it, but, you know, you can modernise it relatively easily because of that, and because all the characters have such a strong connection with each other. It is a relevant piece – it’s never going to be irrelevant. Even the music is not necessarily so old-fashioned. I think that there are some things that are very Romantic, but because of its dramatic arc, it stays really, really modern – and exciting.’

Helping ensure that opera remains modern is clearly something that Tetelman takes pride in. ‘Recently, at LA Opera, I was speaking to some elderly people who have seen opera all around the world for decades, and I asked them, “What is the difference between opera now and then?” And their first response was, “It’s better now.” I asked why, and they said, “It’s just that there is so much more connection to character on the stage now than there was then. And that grips you in the music. Maybe the voice isn’t as big or whatever, but what you’re seeing in terms of production values, and character values, is higher.” I think that’s the key to connecting with future generations.’

A tenor star is born

Talking of looking back, as the noon sun casts its brilliance over the city stretched out below and Tetelman dons some stylish shades, I ask if we might do so on a more personal level. What audiences see is the successful star with the world at his feet, but behind that invariably lies an uncertain path, trodden over many years. What has been his own route to today?

He takes me back to the very beginning. ‘I was adopted when I was six months old, from Chile.’ He grew up in Princeton, New Jersey, where music came into his life: ‘When I was very young my parents noticed that I had some interest in it. We don’t know where it came from – they’re not musicians, and they didn’t really even hear much classical music. But I found this interest in singing very young, and they helped cultivate it by sending me to the American Boychoir School. I got classical training there, learning how to sightread, how to sing in tune. And we toured all over the world, performing with the New York Philharmonic, San Francisco Symphony, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, and we actually made a lot of recordings with them too. So I kind of got my formal “opera” training as this young soloist with the American Boychoir.

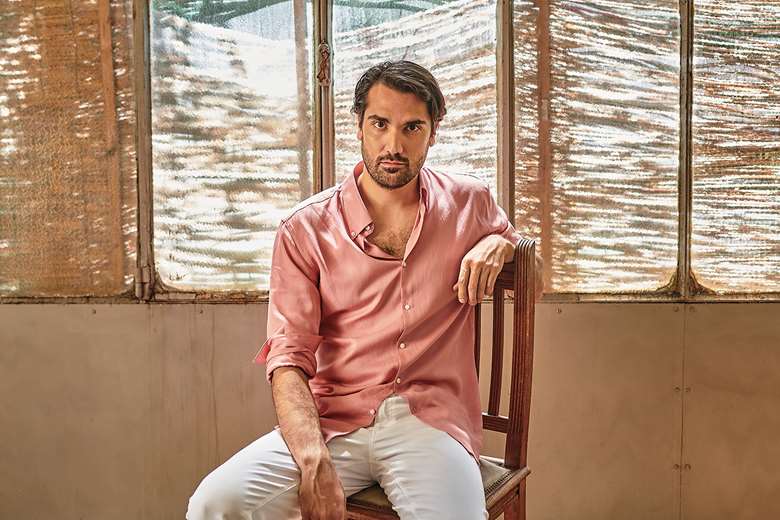

Star Puccini tenor Tetelman’s colourful career includes starting out as a baritone and working as a club DJ and promoter (photography: Ben Wolf)

‘And then my voice changed. I went to high school, and I started a rock band, and I started writing music with this band, singing and playing the guitar. I taught myself guitar, I had to get the attention of the girls! So I did that for a while, and I wanted to pursue some sort of career in music. I wanted to be classically trained, essentially. I thought, “Maybe I’ll be a jazz singer or maybe I’ll sing in the [United States] Marine Band” – it’s a very good life for people. Or maybe I’d become part of the New York Choral Society or the Met Opera Chorus. So I went to the Manhattan School of Music, as a baritone; and that’s actually where I changed my mind. I started to understand what opera was. I went to the Met regularly, and to New York City Opera. I fell in love with this whole opera world and then decided I wanted to become an opera singer. Then I went to grad school, and transitioned to a tenor. I was a horrible tenor. I just wasn’t ready. I was 21.’

Struggling to set aside the memory of that most majestic tenor voice I’d heard mere hours before, I ask him how the move up the register came about. ‘I applied to a bunch of young artists’ programmes and a bunch of grad schools, and they said, “We can’t take you. You’re not a baritone. You’re really a tenor. You’re going to have to come back when you’re ready.”’ Mannes College did, however, give him a place, but ‘it didn’t click’, he recalls. ‘My focus was off. You know, I was kind of heartbroken – I had put all this energy and time into becoming a baritone, learning all this repertoire, and then it’s like I had to start all over again. So I gave up on singing for a while. I was a DJ and a club promoter in New York for three years. Doing that, you’re really an entrepreneur. You have to make all these deals and all these connections by yourself. That was good for me, because I was a bit shy when I was younger, and it really helped me come out of my shell a bit – just going up to people and talking to them in the street, or inviting them to dinner. It was good life-experience – but it was the other 9 to 5: 9pm to 5am, five nights a week. So I just decided, you know, “I’m telling everybody I’m an opera singer. Why am I not becoming an opera singer? I’m lying to myself.” So I found another teacher, and I said, “If in six months I don’t have an agent, I’m not going to continue.” So I worked hard. I had three lessons a week and was learning repertoire. Every day I would learn a new piece, a new aria or a new duet or something. And I was just filling my mind with music and just listening all the time. And, yes, I got an agent in three months. It was all there. All those pieces were there. It just needed to come at the right time. The rest is history.’

Looking ahead now, does he have any sense of what he might be ready for in a few years’ time? ‘I would say five years ago I had a better idea, and now I have less of an idea. It’s really amazing how your mind, with experience, can change so fast. I felt five years ago that I was going to be a big, dramatic tenor, singing all this heavy repertoire. And now I’m in a phase where I don’t want to do that. I’m not tempted by that. I want to do things that allow me to be artistic. It’s not about the role; it’s about what I can bring to the role. You know, there are great operas like Otello and Aida and pieces like that. And I would love to sing them, but right now I think, “What could I bring in terms of my musicianship?” I’ve invested so much of my time and money – and even my family, they give up so much for me to have this career. And so I think taking the right steps is more important than taking the big steps.’

Finally, Tetelman is a figure with that most enviable of recording contracts, a partnership with a major label steeped in heritage, so I ask him what recording means to him, and what he’d like recording to mean to audiences – whether people collecting albums in more traditional ways or a younger generation discovering music on streaming services. ‘It’s a cornerstone of my artistic life,’ he replies. ‘I think recording is valuable because it’s our only connection, in terms of music, to the past – it means you can hear and you can feel it; without recording, it’s tough to really connect. Of course, you don’t have that connection unless you can play the recording – it lets you enjoy the music anywhere. You can just open up your phone and you can listen to something and feel the music. We don’t appreciate what we have any more, because it’s such a normal part of life. Yeah, recording is a special thing.’