Inside Janáček’s Glagolitic Mass

Hannah Nepil

Tuesday, March 15, 2016

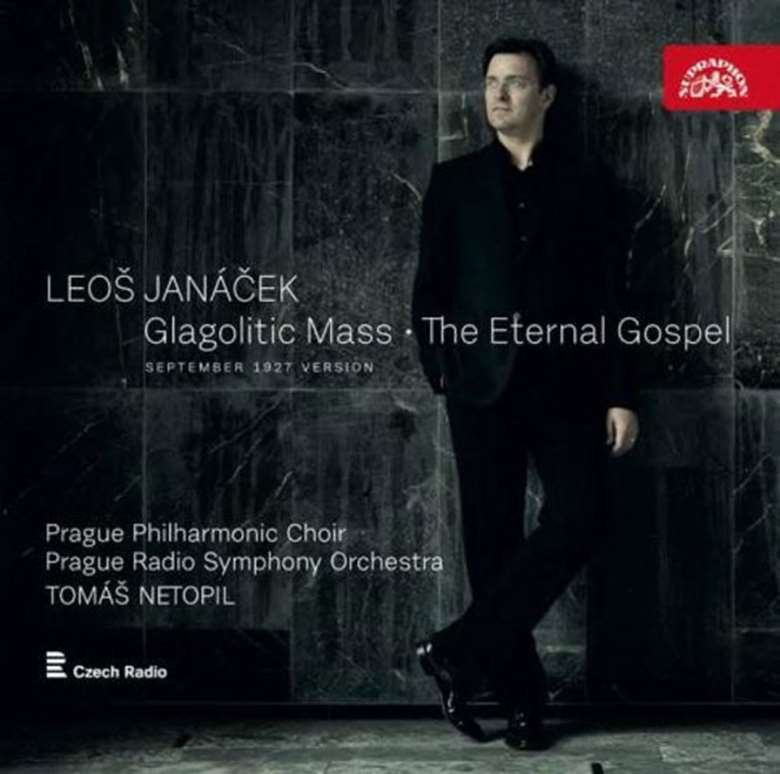

Conductor Tomáš Netopil talks to Hannah Nepil about finding the true spirit of Janáček

Here I am sitting in a floating restaurant on Prague’s River Vltava, singing a Moravian folksong with the conductor Tomáš Netopil and Supraphon’s Chief Executive Producer Matouš Vlčinský. Halfway through, we forget the words. Netopil frowns and reaches into his pocket; a moment later, he’s on his phone beseeching a friend to jog his memory. We’ve only had one glass of wine. And even if we hadn’t, we may well have broken into song: Netopil, 39, was born and bred in Moravia – the eastern, and arguably merrier part of the Czech Republic; this music is in his veins. (My own family is from the former Czechoslovakia which is why I’m able to keep up!) Besides, it’s quite appropriate behaviour, given that we are here to discuss Netopil’s new recording on Supraphon of Janáček’s Glagolitic Mass, a work infused with the essence of the composer’s native Moravia. In Netopil’s view, ‘There is a level of complexity and colour in Moravian folklore which is not quite matched in Bohemia, and which deeply influenced this composer.’ He continues: ‘Janáček came from northern Moravia, where the dialect is very staccato and short – and so often you sense those qualities in this music.’

For the conductor, Janáček’s music is something of a hobby horse: he fell in love with it as a teenager, seduced by its originality and vigour. ‘Janáček was like a lion inside. He loved life and he was very passionate – even in his old age,’ he says, before going on to remind me of the composer’s ardent love for Kamila Stösslová, a married woman 38 years his junior, whom he met aged 63.

That youthful passion is certainly evident in the Glagolitic Mass, despite the fact that this raw, life-affirming piece, based on an Old Church Slavonic text, dates from the last few years of the composer’s life. In the words of the Czech writer Milan Kundera, it’s ‘more an orgy than a mass’. Which tallies with what we know of Janáček’s spiritual outlook: despite growing up in a monastery and acting as a choirmaster and organist for 20 years, he was not a practising Catholic and his attitude towards the Church was ambiguous. ‘He believed in God, but in his own special way,’ Netopil euphemises.

In embarking on this disc, Netopil faced stiff competition. We are already well supplied with recordings of the Mass; the late Sir Charles Mackerras’s 1994 version still stands out for its intellectual rigour and exuberance. But Netopil’s version with the Prague Philharmonic Choir and Radio SO offers something extra: it showcases the latest reconstruction of the original 1927 score, as performed at the work’s world premiere in Brno.

Completed by the Czech musicologist Jiři Zahrádka, it’s not the only ‘original’ version of the score in circulation. That status is also claimed by Paul Wingfield’s well-established edition, which diverges from Zahrádka’s on a number of points. Further complicating matters, both of these differ from the revised edition of the score, which was prepared for the work’s 1928 Prague premiere. Commonly known as the ‘final version’, it is, in Netopil’s view, easier to play than anything that precedes it – but at a cost: ‘It’s less true to the spirit of Janáček.’ Nevertheless, the conductor has taken the odd detail from it – primarily in the interests of practicality.

Only five bars into the Introduction, Netopil was faced with his first dilemma: whether to maintain the septuplet and quintuplet cross-rhythms of the 1927 edition, or to sub-divide the beat more neatly, as per the 1928 version (track 1, 0'07"). He settled on the former option, because, although far more taxing for the performer, it provided greater scope for contrast: ‘In the first few bars you know exactly what the beat is and then suddenly you get three bars of chaos. And these two worlds are fighting each other throughout the first movement. For me that’s real Janáček – this juxtaposition of two strong, rhythmical colours. If you package everything into one neat rhythmical system, you lose that.’

Indeed, few would describe Janáček’s music as ‘neat’. This helps to explain Netopil’s approach to the second movement ‘Gospodi Pomiluj’, where the early and later editions of the score differ in metre, the former being in five, the latter in four. ‘Although it is much easier to play in four, I stuck with Janáček’s first instinct, in order to convey the insecure feeling of the music at this point.’ Netopil also preferred the sparser orchestration of the original because, as he says, ‘Janáček is not romantic; his music is strong and dry. And within this dryness you will find lyrical passages that make more of an impact if they contrast with what surrounds them.’ Only occasionally does Netopil prioritise the later edition of the score, for example at bar 63 (track 2, 2'26") where he favours a higher register for the soprano part to ensure its audibility.

The third movement – ‘Slava’ – provokes further thoughts on orchestration. Netopil emphasises the importance of highlighting the ‘desperate scream’ of the horn at bars 66-69 (track 3, 1'55"), a detail obscured when Janáček later added a thunderous timpani part: ‘The music sounds more primal without the timpani; more like Janáček.’ Similar reasoning underpins his decision to use solo timpani in the last bars of the movement (track 3, 5'57") rather than adopting the composer’s later revision and adding an organ accompaniment. ‘If you leave out the organ it sounds more like The Rite of Spring at that point – more natural; not really like divine music.’

By the time we reach the ‘Vĕruju’ our conversation has turned to text setting. This movement showcases Janáček’s facility for mirroring the contours of the Czech language – a characteristic that the conductor was keen to draw out. ‘I tried to premeditate the staccato articulation of lines such as “vje-di-no-go Bo-ga” (“in one God”) (track 4, 0'22") by mimicking it in the orchestral part.’

The most challenging part of this section, however, arrives at figure 9, where the original score introduces a rapid-fire dialogue between the orchestra (complete with three timpani) and organ (track 4, 5'53"). As the conductor explains, Janáček eventually cut this passage, perhaps to avoid the expense of hiring three timpanists. Netopil, however, was determined to preserve the primitive sound of the timpani, which is a key characteristic of Janáček’s music, invaluable in the openings of such works as The Makropulos Case and Kát’á Kabanová.

Our time is almost up, but in the last few minutes, Netopil turns to the final movement. The Intrada – as he tells me – is a subject of some dispute. There are those who insist on performing it twice – at the work’s opening and conclusion, and, in fact this movement did bookend the work at its 1927 premiere. But whether this was the decision of Janáček or the conductor remains undetermined. Netopil’s preference was to save the Intrada for the grand finale. After all, he says, it would be a pity to unleash it too early in the game: ‘It would ruin the surprise.’

The historical view

April 12, 1928

A letter from Janáček regarding the Glagolitic Mass’s Prague premiere

‘We did not take the path trodden by slippers. We surely did not sow rotten seeds. We stood out in the programme like a sore thumb, but it was necessary. We were a fresh spring breeze.’

October 24, 1930

The Daily Mail on the British premiere of the work at the Norwich Festival

‘Norfolk people, known for their placidity, were not to be expected to capture the spirit of boisterous Bohemian rustics…If the music suggested any religious occasion it was the dedication of a new railway station.’

July 2014

Composer Julian Anderson talking about the Glagolitic Mass on BBC Radio 3

‘I think Janáček was one of the most original thinkers in terms of [his] instrumental sound…the sheer impression it makes on the listener is utterly distinctive and very odd. It should not be tamed.’