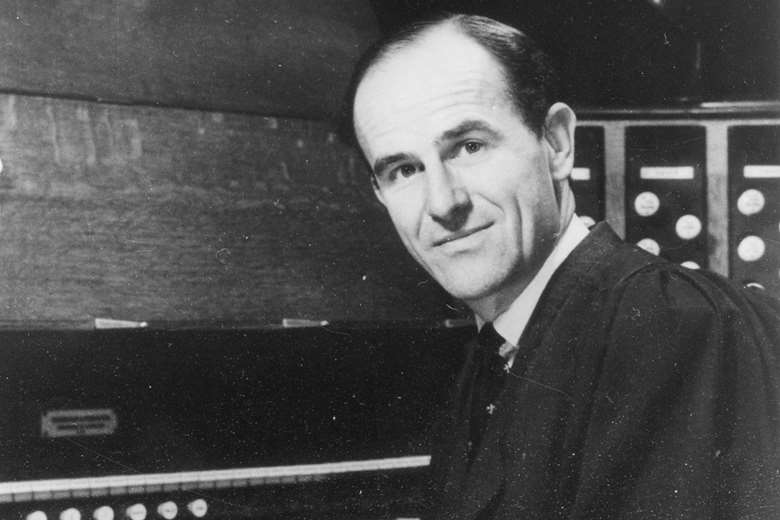

Icon: Sir David Willcocks

Richard Osborne

Friday, November 29, 2024

Richard Osborne pays tribute to the master choral conductor associated with august institutions including the Choir of King’s College Cambridge and the Bach Choir

Register now to continue reading

Thanks for exploring the Gramophone website. Sign up for a free account today to enjoy the following benefits:

- Free access to 3 subscriber-only articles per month

- Unlimited access to our news, podcasts and awards pages

- Free weekly email newsletter