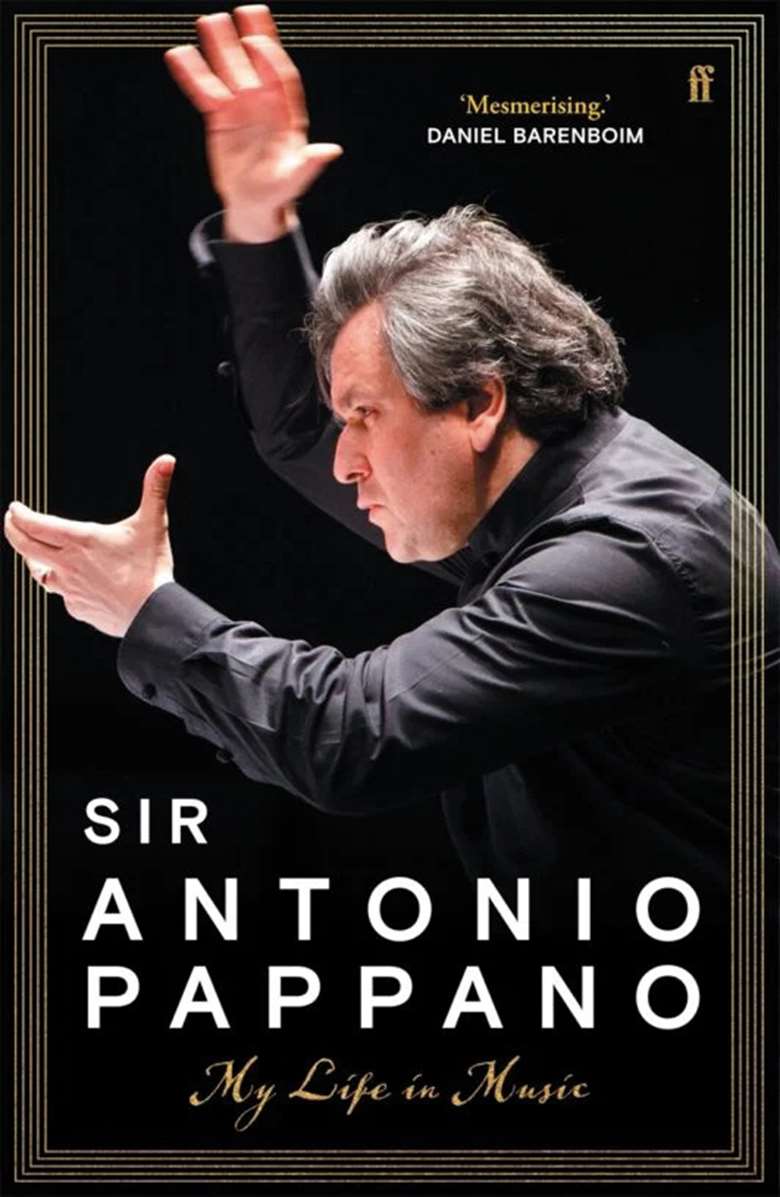

Book review - My Life in Music, by Sir Antonio Pappano

Richard Bratby

Friday, June 14, 2024

There are professional music writers who could do worse than learn from Pappano's example

There are two basic types of musician memoir. There’s the indiscreet kind, by artists who are too big, too forthright or simply too retired to worry what people think: Berlioz’s explosive score-settling or Simon Rattle (in Nicholas Kenyon’s biography) furiously savaging the idiocies of the Arts Council. Then there’s the kind written by musicians who still have skin in the game – with careers to tend, colleagues to consider and PRs looking over their shoulders. Reading them, I’m reminded of how my first boss at the Liverpool Phil advised me to reply when asked for my opinion of an artist (at least, if I valued my career): ‘Nice guy, wonderful musician’.

Having headed London’s Royal Opera and the Orchestra of Santa Cecilia in Rome for most of this century, Antonio Pappano is now about to succeed Rattle at the helm of the London Symphony Orchestra, and there’s nothing in My Life in Music that will startle any horses. Pappano has an interesting story to tell regardless, and the tone of his autobiography is much as you’d expect from such a seasoned communicator: unaffected and direct, with an easy, non-technical style that conveys – nonetheless – a huge depth of insight and musical experience. There are professional music writers who could do worse than learn from his example.

Pappano’s descriptions of his early life are undeniably touching, and if you’ve ever wondered how a boy with an Italian name and heritage came to acquire both a mid-Atlantic accent and a place at the pinnacle of the British musical establishment (Pappano describes his involvement in the 2023 coronation of King Charles III), well, here’s the definitive account. His parents emigrated from rural Italy to London in the 1950s in search of ‘more from life than the village had to offer’. Antonio was born in Essex, and while he bashed on an upright piano in the family’s London flat, his father sublimated his ambitions as a tenor into a career as a singing teacher – with his son, in due course, assisting him as accompanist.

That early experience permeates much of what follows: through the family’s subsequent emigration to the US, Pappano’s involvement with a small Connecticut opera company and his dawning realisation that a career as a repetiteur was a possibility. His horizons expand to New York (it’s intriguing to learn that he worked with the great Broadway producer Hal Prince) and then to Europe, his excitement mingling with guilt at leaving his father pianist-less. ‘You play the piano like an orchestra; you have to conduct’, says the Danish soprano Inga Nielsen. And of course, that’s what Pappano eventually does – but not before working in Oslo, Barcelona and Frankfurt and assisting Barenboim at Bayreuth.

Fascinatingly, what Pappano describes is the sort of on-the-job training associated with the young Bruno Walter or Karajan, and which you might have assumed was impossible by the 1980s. Here’s the young assistant Kapellmeister, thrown in at the deep end, discovering new scores at the piano and learning from hands-on experience what makes singers stumble or soar. And, of course, making mistakes – like a Vienna Siegfried where he fails to click with the orchestra but the show has to go on regardless. ‘Well, who else are we going to find at this short notice?’ grumbles the concertmaster. Pappano’s extended descriptions of the intricacies – both psychological and technical – of assembling an operatic production will fascinate experts and amateurs alike.

Pappano gives brisk, appreciative accounts of his successes and colleagues at the companies he’s headed (La Monnaie in Brussels, as well as the Santa Cecilia orchestra and the Royal Opera) but this isn’t the place to look for gossip or controversy. If he’s given much thought to the issues that have blighted Plácido Domingo’s later career in the US, he doesn’t say so, and his observations on the current funding crisis facing opera in the UK (where his colleagues might reasonably have hoped for the gloves to come off) are mild to the point of being innocuous.

But Pappano has always been a collegial figure – an enthusiast, for whom the company and the music come first – and possibly that wasn’t the book he meant to write. Some of the later chapters sit oddly together: a reader who can follow Pappano’s (fascinating) note-by-note analysis of Verdi’s Requiem is unlikely to need a plot summary of Le nozze di Figaro. But Pappano is about to begin a new chapter in his career; and perhaps some things belong in a postscript. ‘I am truly blessed to have this life’, he concludes, and you can see why. Nice guy, wonderful musician.

This review originally appeared in the July 2024 issue of Gramophone. Never miss an issue of the world's leading classical music magazine – subscribe to Gramophone today