Benjamin Britten, Ruth Gipps ... and Jeoffry, the Poet's Cat

Oliver Soden

Friday, October 16, 2020

Oliver Soden explores the links between a celebrated 18th century cat, and music closer to our own time

At the close of what W.H. Auden called the ‘low dishonest decade’ of the 1930s, an American diplomat named William Force Stead paid a visit to a friend’s country house and discovered in its library a manuscript that had been lost for centuries: Christopher Smart’s visionary poem Jubilate Agno, written between 1759 and 1763 during Smart’s incarceration in a lunatic asylum. The set of large dusty sheets was incomplete, but the 1,739 lines of verse that had survived were still an epic hymn of praise: ‘Rejoice in God, O ye Tongues; give the glory to the Lord, and the Lamb’.

The poem hovers between the absurd and the sublime, simultaneously a magnificat and an asylum journal. For company and solace during his confinement Smart seems only to have had his cat, the immortal Jeoffry, to whom he devoted an enchanting seventy-four lines of rapturous description: ‘For I will consider my cat Jeoffry…’ The ‘Jeoffry’ section of Jubilate Agno is now thought to be the most anthologised verse in the language.

It was at Auden’s suggestion that, in 1943, Benjamin Britten used sections of Jubilate Agno for a cantata to satisfy a choral commission from Walter Hussey, vicar at St Matthew’s Church, Northampton. Britten was not turning to an established eighteenth-century text but to a newly unearthed and still controversial poem. Smart’s work was exciting and perplexing some of the great modernist poets of the day; readers were slow to work out the method in its madness. Britten’s Rejoice in the Lamb was premiered at St Matthew’s on 21 September 1943, in the mid-war hush between the Blitz and the doodlebugs.

‘I am afraid I have gone ahead and used a bit about the cat Jeffrey’ Britten told Hussey, never entirely grasping the idiosyncratic spelling of the cat’s name (he had to scratch out a superfluous e from the manuscript score). ‘He is such a nice cat.’ And so he is, memorably described by Smart as ‘surpassing in beauty’, a ‘mixture of gravity and waggery’ who can tread ‘to all the measures upon the musick’, his tongue ‘exceeding pure so that it has in purity what it wants in musick’. Britten gave the Jeoffry section to a treble, and the organ frolics around the vocal line in E-major loops, a scatter of semiquaver pawprints.

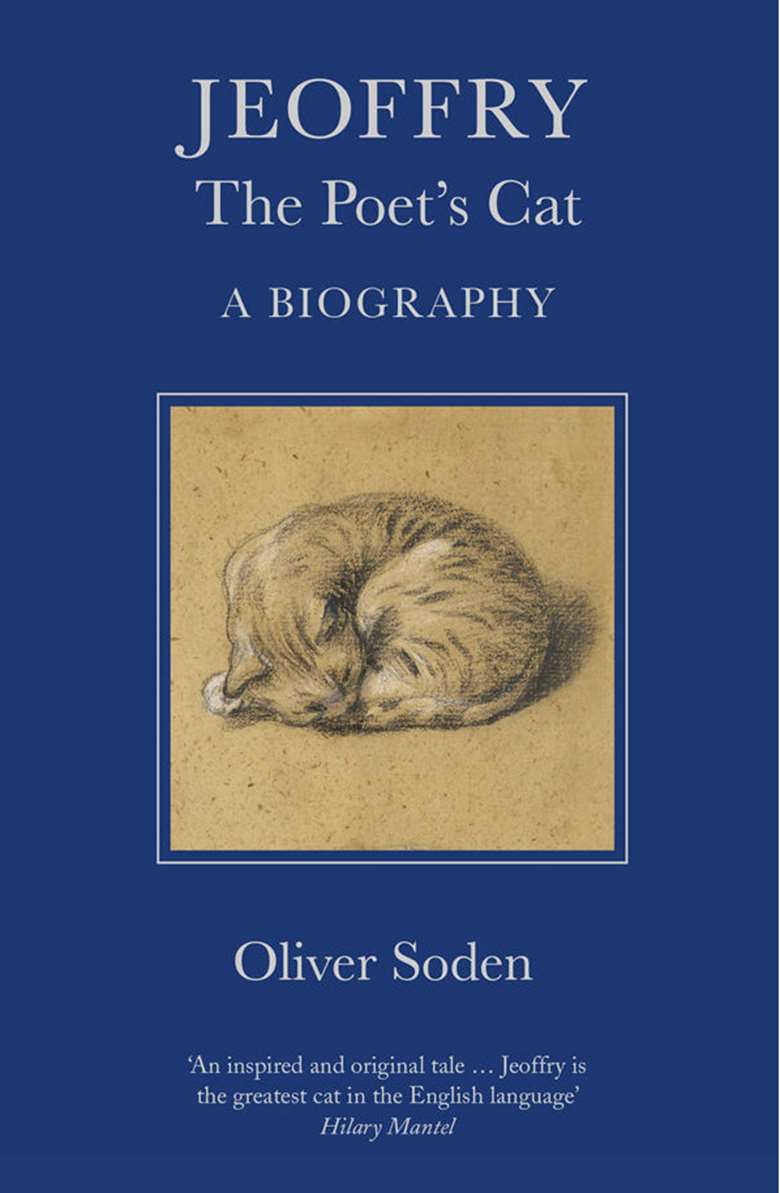

Immortalised in words and in music this real cat, who lived in an asylum 250 years ago and doubtless met some of the great figures of the age as they visited Smart in his cell, seemed to me a prime candidate for a biography. Drawing on the model of Virginia Woolf’s Flush, her life of Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s spaniel, I could dress a framework of facts with flights of fictional fancy. The book – Jeoffry: The Poet’s Cat – did not prove all that big a leap from my previous biographical subject, Michael Tippett, who sang tenor in the first performance of Rejoice in the Lamb and then conducted its first radio broadcast. (Unlike Britten, who favoured dachshunds, Tippett was a cat lover, one of whose cats met a sad end at the hands of a black-souled neighbour.)

The book also explores the ways in which Jeoffry has inspired any number of creative artists. Britten’s musical portrait of Jeoffry has become so indelible that few composers have dared encroach on the territory. But the cat was given a new lease of life when in 1952 Britten’s musical assistant, Imogen Holst, orchestrated Rejoice in the Lamb. Nicely sharpening any potential for sugariness in the original, she allocated to Jeoffry the jazzy feline slink of the clarinet, forever the cat’s instrument after Peter and the Wolf – Britten’s early musical debt to Prokofiev was revealed afresh.

Less well known is a cantata for four-part choir called The Cat by Ruth Gipps, which sets Smart’s portrait of Jeoffry for its finale (other sections use cat verse by Swinburne and by Michael Joseph). The piece has earned a permanent footnote in musical history for being the first composition by a woman to be accepted for a doctorate. But even as Gipps’s symphonies enjoy a revival there is no recording of The Cat, and precious few copies of the score survive.

Gipps clung resolutely to tonality and intemperately dismissed composers who didn’t. But Jubilate Agno itself is strangely atonal. In its intricate puns and patternings, its symmetries and mirror images, it would lend itself beautifully to the dodecaphonic close-weave of serialism: the wide sonic embrace of ‘pantonalism’, as Schoenberg had it, would suit this most pantheistic of poems, which sees God in all, and all in God. Or might a dramatic monodrama be imagined, a descendent of Peter Maxwell Davies’s Eight Songs for a Mad King, with animals in cages and Baroque quotations heard, as it were, through the wrong end of a telescope amid a heap of broken instruments?

New settings of Smart’s poetry can also be a useful reminder that Britten, reading Jubilate Agno in 1943, did not know, and could not have known, how it worked. The poem is made of lines beginning with ‘Let…’, and lines beginning with ‘For…’, and only in the 1950s did an editor realise that the ‘Let’ and ‘For’ sections were linked antiphonally, a call-and-response sequence. (The ‘Let’ lines that must have accompanied the section about Jeoffry are lost.) So an intrinsically musical effect at the heart of Jubilate Agno had yet to be harnessed by a composer.

When Jeoffry: The Poet’s Cat was published a concert was held in the Aldeburgh Parish Church (see below), where Britten and Peter Pears are buried in the graveyard and where, on the end of a pew by the organ, you can find a small wooden cat. There was a premiere of a new piece, simply titled Jeoffry, by Arthur Keegan-Bole, for tenor, mezzo-soprano, and electronics. Setting lines from Jubilate Agno, it made full use of the poem’s structural stereophonics, the ‘dec’ and ‘can’ duet of Smart’s ecstatic to-and-fro between ‘let’ and ‘for’.

Smart wrote that, stroking his cat, he had ‘found out electricity’. He believed it, too: scientists of his century thought that cats generated electricity when they purred. So the electronic spangles of Keegan-Bole’s accompaniment were especially apt, as they morphed into cat yowls and tiger roars, and the splash of falling rain, in which Smart danced naked in praise of his God. There was even the electric ripple of a little organ call, snipped from a recording of Britten’s cantata. Keegan-Bole entwines E major and E-flat major like two cats huddling for warmth. The poem itself – its strange feline mixture, in Smart’s words, of ‘gravity and waggery’ – suddenly seemed a sonic exercise in bitonality. As with all the best settings of poetry, the words were liberated by music rather than imprisoned within it like a mad poet in a cell. The music inherent in Smart’s verse was illumined anew.

Socially distanced on the cold pews, we considered once again the cat Jeoffry, as he trod to all the measures upon the musick. For there he was.

Jeoffry: The Poet’s Cat is published by The History Press and available now.

Michael Tippett: The Biography ('nothing short of miraculous' – Gramophone, reviewed in July 2019) is now published in paperback on 15 October.