An introduction to Mussorgsky's 'Pictures from an Exhibition' and Prokofiev's 'Visions fugitives' and 'Sarcasms', by David Fanning

James McCarthy

Monday, August 19, 2013

’Woe to orphaned Russian art’, declared Modest Musorgsky in the summer of 1873. His friend, Viktor Hartmann—an aspiring architect, designer and painter—had just died of an aneurysm in his late thirties, and Musorgsky had lost one of his companions-in-arms in the search for something radically new and authentically Russian in the arts. Vladimir Stasov—the man of letters who in May 1867 had coined the term ‘The Mighty Handful’ for Musorgsky and four of his fellow-composers of nationalist persuasion—mounted a memorial exhibition of Hartmann’s designs, watercolours and drawings, most of them produced during the artist’s trips abroad. And it was this occasion that prompted Musorgsky to compose one of the most original and challenging works in the piano repertoire and to dedicate it to Stasov.

Pictures from an Exhibition (for some reason the common mistranslation of Musorgsky’s ‘from’ as ‘at’ has proved hard to dislodge) was composed rapidly in the first three weeks of June 1874. It consists of musical representations of eleven of Hartmann’s works, six of which have been preserved in various archives and can be seen in a number of modern re-publications of the work (the ‘Two Jews’ were originally two separate paintings). In a Preface to the first publication of Pictures, Stasov left helpful descriptions of each object, which are all we have to go on for those since lost. That edition, which appeared in 1886, five years after the composer’s death, came with emendations by Rimsky-Korsakov; and it was from this well-meaning but somewhat bowdlerised version that Ravel made his famous orchestration in 1922. Publication in Musorgsky’s original form had to wait until 1931.

To help assemble his ten ‘pictures’ into a coherent musical ‘exhibition’, Musorgsky decided to depict himself, too, as if walking from one display to another in various moods, in a series of what he called Promenades. The first of these is styled additionally ‘in modo russico’, presumably because of its changing time signatures and folksong motifs. After this sturdy introduction the composer as it were rounds a corner and finds himself confronted by the first object on display, ‘Gnomus’. According to Stasov, this was a design for a grotesque nutcracker, in the form of a dwarf on deformed legs and with huge jaws. A chastened form of the Promenade then ushers in ‘Il vecchio castello’, depicting a troubadour singing over a drone bass in front of a medieval castle.

A renewed confident stride brings us quickly to ‘Tuileries’, which represents children squabbling and playing in the avenues of the famous Parisian gardens. With no intervening Promenade, ‘Bydlo’ depicts a Polish ox-cart on huge wheels, to which Rimsky-Korsakov made one of his most cavalier amendments, changing Musorgsky’s initial fortissimo to pianissimo, perhaps with the idea of the cart slowly approaching and receding, rather as in the Funeral March of Chopin’s B flat minor Sonata with its similar implacable harmonic foundation. Then a Promenade in the piano’s higher register anticipates the quicksilver humour of the ‘Ballet of the unhatched chicks’, a response to one of seventeen Hartmann illustrations for the ballet Trilby, with choreography by Petipa and music by Julius Gerber (the scene was apparently danced by children of the Imperial Ballet School, their arms and legs protruding from egg-shell costumes). Again without a break we move into ‘Samuel Goldenberg and Schmuyle’, a conflation of two portraits made during Hartmann’s visits to Sandomir, Poland, depicting a rich and a poor Jew. Musorgksy’s original title was for long suppressed, presumably because it provided an uncomfortable reminder of the casual anti-semitic attitudes he shared with large numbers of the Russian aristocratic intelligentsia of the time.

At this point the pianist has to take a deep breath, because the rest of the work plays without a break, and its technical demands steadily increase. A texturally enriched version of the opening Promenade introduces ‘Limoges, the market place’, subtitled ironically ‘The Big News’ (Musorgsky’s crossed-out annotations concern chit-chat over a runaway cow). After this fuss and bother, we are plummeted into the ‘Catacombae’ beneath Paris, coming face to face with an ancient Roman burial-ground (the second part of this memento mori, in which the Promenade theme appears beneath chilling tremolandos, had no title in the original). The ghoulish vein is developed with a musical depiction of Hartmann’s design for a clock in the form of a ‘hut on fowl’s legs’, titled ‘Baba Yaga’ after the evil witch of Russian folklore. The cycle is crowned by a grandiose aural realization of Hartmann’s design for ‘The Bogatyr Gate in Kiev’ (better known as ‘The Great Gate of Kiev’). The Bogatyrs were medieval warrior-nobles, and Hartmann’s gate, which was never actually built, was to have featured a bell-tower in the shape of a gigantic helmet—clearly the inspiration for Musorgsky’s spectacular, tintinnabulating textures.

For composers from Schubert to the present day the attractions of the piano miniature have been broadly similar. It has a better-than-average chance of being taken up by young or amateur players; it therefore stands a better-than-average chance of being published; for the composer-performer it fits snugly into recital programmes, where it may serve as an advertisement for and introduction to other compositions; and it may provide a useful testing-ground for compositional ideas, prior to their potential deployment in more demanding large-scale forms.

In their various contrasting ways, the twenty miniatures that make up Prokofiev’s Visions fugitives display all those qualities, and they have always been among the most popular of his piano pieces. The title of the collection is a poetic rendering of the Russian Mimolyotnosti (literally ‘things flying past’, or more pretentiously ‘transiences’) from the poem ‘I do not know wisdom’ by the symbolist Konstantin Balmont. Taking his cue from the lines ‘In every fugitive vision / I see whole worlds: / They change endlessly, / Flashing in playful rainbow colours’, Prokofiev supplies snapshots of his most characteristic moods—sometimes grotesque, sometimes incantatory and mystical, sometimes simply poetic, sometimes aggressively assertive, sometimes so delicately poised as to allow the performer and the listener to make up their own minds.

The Visions were assembled between 1915 and 1917. In his 1941 autobiography Prokofiev claimed that No 19 reflected the excitement of the crowds at the time of the February 1917 Revolution (which deposed the tsar—the more famous ‘October’ Revolution, establishing Bolshevik rule, followed later the same year). But that claim may be a case of self-reinvention aimed at a Soviet readership. Without that information, the same could as easily be said of Nos 4, 14 and 15. In 1935 Prokofiev made recordings of ten pieces from the set, and his playing is notable for its wistfulness, subtle shadings and—in places—rhythmic freedom. Even the clowning of the Ridicolosamente No 10 is rather shy in Prokofiev’s hands, and the delicacy he brings to the following piece brings out its affinities with Debussy’s Minstrels.

Standing rather apart from the salon pieces, Impressionist evocations and fairy tales that make up the bulk of early twentieth-century piano miniatures, there are also some that have their sights set more on innovation and experiment. Prokofiev himself gave one of the earliest performances of Schoenberg’s Three Piano Pieces, Op 11 (1909), and Bartók’s uncompromising Burlesques (1908–11) and Allegro barbaro (1911) enjoyed considerable notoriety at the time. Prokofiev’s own Sarcasms, composed between 1912 and 1914, are more or less in this mould, and they are certainly among his most experimental works before his period of self-imposed exile from 1918.

No doubt there was an element of image-consciousness here, too, right from the beginning. Prokofiev revelled in the controversy provoked by his more extravagant compositions and performances. In 1941 he reflected on the fifthSarcasm, perhaps again with a degree of hindsight: ‘Sometimes we laugh maliciously at someone or something, but when we look closer, we see how pathetic and unfortunate is the object of our laughter. Then we become uncomfortable and the laughter rings in our ears, laughing now at us.’ But there is no need to take these compositions too seriously. Equally plausible is the response of the noted Russian virtuoso Konstantin Igumnov to the same piece: ‘This is the image of a reveller. He has been up to mischief, has broken plates and dishes, and has been kicked downstairs; he lies there and finally begins to come to his senses; but he is still unable to tell his right foot from his left.’

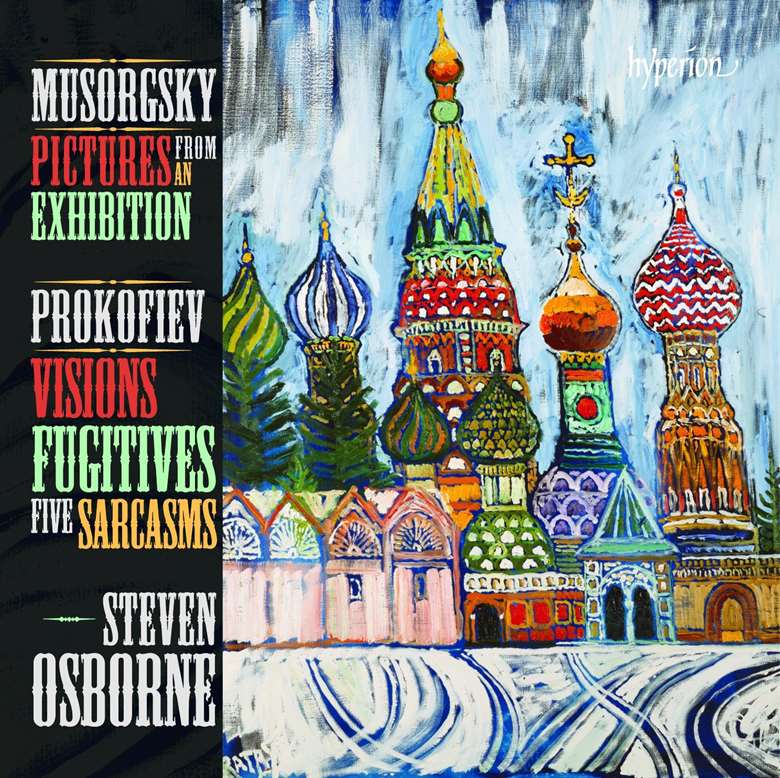

Booklet-note reproduced with kind permission from Hyperion Records