An interview with Arvo Pärt and his closest musical collaborators

Gramophone

Thursday, July 7, 2016

A classic interview from the September 1996 issue of Gramophone, by Nick Kimberley

In classical music, popular success begets critical disdain. In the last 20 years, the music of the Estonian composer Arvo Pärt has touched audiences all over the world. Like many composers before him, Pärt sees his music as an expression of his religious convictions, in his case Orthodox Christian. Certainly the majority of those moved by his music don't share those beliefs, yet critics deride his work as 'Holy Minimalism'. They portray the composer as an earnest aesthete, and, it has to be said, those who champion his music sometimes collude: the booklet accompanying the recording of his Passio, released by the German label ECM, includes a photo of Pärt's hands, as if in contemplation of a living saint.

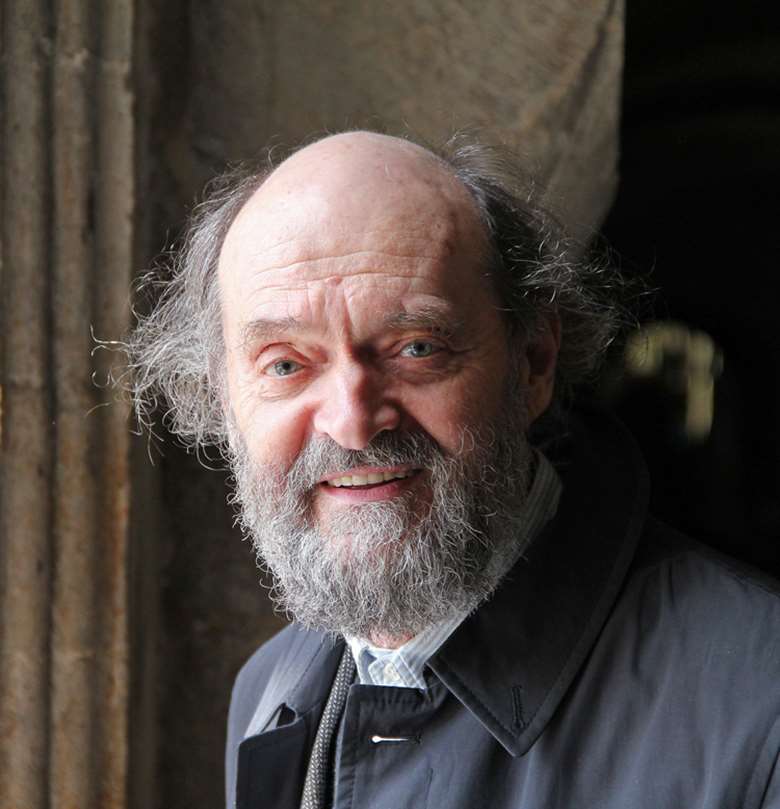

In person the composer presents a different figure. Certainly he is serious but there is also a lively, self-deprecating and disarming wit. In June I met Pärt at a recording session in Stockholm where Paavo Järvi was conducting the Royal Stockholm Philharmonic's Virgin Classics recording of Nekrolog, written in 1960 when the composer was in his mid-twenties. After a play-through of the piece, composed in a jagged expressionist style far removed from his current music, Pärt threw up his hands in mock exasperation and exclaimed, 'I don't understand why young people like such noisy music!' At the end of a successful day's recording, the composer, conductor and recording team adjourned to one of Stockholm's smarter restaurants, where a sumptuous and beautifully presented meal elicited from Pärt the observation, delivered with wry solemnity, 'A music student could learn more from this meal than from a bad music teacher.'

Food, it seems, plays a significant part in the composer's life. Two weeks later we met again when he was in Norwich to see the cathedral choristers premiere his I am the True Vine. Just before a rehearsal, I sit down with Pärt and his wife. Not quite sure what kind of answer to expect, I ask, 'What do you do to help you through periods when writing music is difficult?' The reply is cautious. 'It's very rare that writing music is easy. But you should ask my wife: she suffers more in these cases than I do.' Frau Pärt suggests that, when the going gets tough, the composer gets into the kitchen, where he starts cooking. Arvo Pärt laughs. 'I peel potatoes, that calms me down.' Frau Pärt adds, 'Even when we don't need potatoes.' The image of the composer surrounded by bucketfuls of unwanted peeled potatoes will stay with me a long time.

Arvo Pärt was born in Estonia in 1935. In 1939 the Nazi-Soviet Pact handed the country to Stalin, and Pärt grew up under Soviet rule. That did not preclude a sophisticated musical education. He studied with the composer Heino Eller, whose teaching provides a thread running through modern Estonian music. Besides Pärt, Eller taught the great symphonist Eduard Tubin, who left Estonia in 1944; and his last student (Eller died in 1970) was Lepo Sumera, one of Estonia's leading contemporary composers. By no means a modernist, Eller was tolerated by the Soviet authorities, and Pärt recalls him fondly: 'There is only one central composition school in Estonia, and it's Eller's school. He gave me a path, but this path was very broad. He didn't push in any direction, he supported you even if what you wrote wasn't exactly like his own credo. He was very human, and it was a vivid apprenticeship.'

Still, it was not easy to be a composer in Estonia. In 1961, Pärt wrote what is widely acknowledged to be the first piece of Estonian serial music, his oratorio Maailma samm ('The Stride of the World'), a work no longer included in the composer's catalogue. The authorities regarded serialism as Western and decadent, and Pärt could not but come into conflict with those who controlled musical life, especially since much of his work was overtly religious. For many years he made his living working in radio and film, while writing music that struggled to find an audience. He abandoned serialism in the late 1960s, and a period of close study of medieval music led in 1976 to the style which Pärt labels 'tintinnabular' in recognition of his quest for a bell-like simplicity. Eventually the unending frustrations of Soviet life caused Pärt to emigrate in 1980, and he has lived in Berlin since 1982. His music continues to develop, but remains recognizably in the tintinnabular mode he discovered 20 years ago.

Understandably perhaps, Pärt is reluctant to talk about his life in Soviet Estonia, but his contribution to the country's musical life is readily acknowledged by others, some of whom had no less painful experiences. The conductor Neeme Järvi left Estonia at the same time as Pärt because, he says, 'I no longer had the possibility of serving Estonian art'. He has long promoted Pärt's music, including pieces written before the composer's tintinnabular style emerged. He recalls the problems he faced in getting the music performed: ' Pärt was, and still is, an adventurous composer, and a religious man. That was bound to cause problems during the Soviet era, and he simply couldn't make a living from being a composer. Under Soviet rule, every piece had to be shown to the Union of Composers before it was performed. I remember conducting his Credo in 1968, and of course it has a religious text. It was a huge success, but I didn't get a permit from the Union. Religious music was not permitted, so the next morning there was a big scandal. That was simply how it was then.'

Perhaps the official criticism of the piece hastened his decision to abandon serialism, for the Credo was Pärt's last serial work. Yet despite the long history of conflict, Pärt's music did find an audience in Estonia. Tonu Kaljuste, who conducts the performance of Litany on the new CD of Pärt's music, recalls encountering Pärt 's work at a very early age. 'I remember singing his cantata Our Garden as a member of a choir of 10,000 children taking part in the Estonian Children's Song Festival. It was a piece that gave pleasure to everyone who sang it. In fact, children still perform the piece today. My father, who conducted that performance, was very happy that a young composer, working in the Soviet era, could write such sincere music for children. There is in Pärt's music a sincerity that you could call childlike, even in the music he writes now. He writes in different languages, for different churches, but we must never forget the influence of the spirit of Orthodox church music. Whether in his vocal music, or his orchestral pieces, he is composing prayers.'

It is Pärt's vocal music that has won him the greatest appreciation. In giving expression to his innermost convictions, it can be seen as the core of his work. As Pärt himse lf says, 'The human voice is the most perfect instrument of all, the instrument that is closest to us, and we respond to its finest nuances. The words are very 'important for me, they define the music. The intonations, phrases, pauses, almost all the parameters of the text, have an important meaning. One can say that the construction of the music is based on the construction of text.'

Yet words don't come easily when Pärt talks about his music, and not only because our conversation is conducted in German, a second language for him, something rather less for me. His reluctance to discuss his work goes deeper than that, and when I ask whether he has anything to say about Litany and the other pieces o the new CD, he replies , 'My best recommendation is that Gramophone readers have a gramophone! Talking about my music traps me in a vicious circle and it's very seldom that I manage to escape it. If I'm writing a new piece then I mustn't talk about it because if I do then I have no impulse to write it any more. Once it's written, then there is nothing left to say. That's very apparent to me. It 's a matter of thinking in music, and I hope my music finds a direct way to the listener without any further explanation.'

Over the years , Pärt 's music has attracted performers who return to his work repeatedly, drawn by the demands and rewards of playing it. Christopher Bowers-Broadbent, a formidable exponent of new music for the organ, recalls his first encounter. 'It was about 15 years ago. The Hilliard Ensemble was preparing a broadcast for the BBC, and the producer rang up and said, 'We need an organist, a nd you're the only one I know who plays contemporary music.' I was used to playing music that you needed to study months in advance, so I told Paul Hillier of the Hilliards that I wanted some scores. Paul said, 'No, there's no problem, it's very straightforward, you can sig ht-read it all .' I turned up at the session and was completely stunned: here was a man who, in the best way, was articulating something that many people, composers, musicians, and audiences, were moving towards. More often than not, the simplest music is the hardest to perform. I often think "God, I wish I had more notes: this is exhausting to play."

'And it's emotionally draining. The performer needs enormous poise. I used to ask Arvo, "What speed should I play this piece at?" And he'd say, "What speed do you want? Play your heartbeat." That's not a cop-out, it's a very sensible reply. If you look at the score and think, "This should be played at crotchet=such-and-such", you've approached it in the wrong way.'

Paul Hillier now lives and works in California, where his ensemble Theatre of Voices has recorded a CD of Pärt 's music, to be released next spring by Harmonia Mundi. He has also completed a book on the composer's music, which will be published by Oxford University Press. He recalls his first meeting with Pärt: 'In the early 1980s I read an article by Susan Bradshaw, which encouraged me to get in touch with Arvo's publisher and ask to see some scores. That in turn encouraged him to get in touch with me and we met up: on Victoria Station, of all places. We talked, looked at scores, and some thing leapt out at me: this was the kind of music I had been waiting to perform. There was an instant recognition; the scores revealed, if you like, that they had much more to reveal.'

Like Bowers-Broadbent, Hillier is careful to point out that, despite that immediate impression, 'In a sense, the scores are empty, and I like their economy. At the same time, they're pregnant. It's not hard to get the notes right, to play or sing across the top of the music, making very beautiful sounds: what do you do next? It's only when you dig deeper that you pull something to the surface. Sometimes I rehearse a piece at a much slower tempo than the one at which I will perform it, just to see what forces itself to your attention that might otherwise go unnoticed. The interpretation is there to discover, to develop, to change over the course of time. And Arvo's own ideas change. That's healthy. I like it that not everything is fixed.'

Paul Hillier's place in the Hilliard Ensemble has been taken by Gordon Jones, who sings on the ECM recording of Litany, a piece written for the Hilliards. Jones vividly describes his encounter with the work: ' Like a lot of Arvo's music, Litany sounds terribly simple, but there are moments which are rather frightening. You have to be so still, so accurate; and some times you have to sing very quietly and very high at the same time. The technical demands are great, but not obvious. It's not like singing at full tilt, or singing a lot of incredibly high notes. It 's a matter of control: the stillness of the music suits the way we sing.'

That stillness is the central experience of Pärt's music, and it is an experience that has left its mark on other composers. The English composer/performer Gavin Bryars has written that 'the revelation of [Pärt's] music has been one of the most important factors in the development of a new sensibility in recent music.' That same opinion he reiterates now. 'The first music of Arvo's that I heard was the ECM recording of Tabula rasa. I found it surprising, but a confirmation of my own concerns. This was music that was about a state of affairs, rather than a narrative, or a logical argument, and that impresssed me immensely. Later, when Arvo was featured composer at the Almeida Festival in London in 1986, I had the chance to play the piano part in that piece; that was very rewarding, and rather nerve-wracking. It certainly opened up the piece for me. He's such a refreshing voice, and he has a fantastic ear. Remember that in Estonia he worked in radio and film, where you need an ear for the precise effect that suits each particular mood.'

Bryars insists that sharing Pärt's religious convictions is not integral to appreciating the music: 'Bach's St Matthew Passion moves me without me being a Lutheran Christian. Sometimes, in fact, I find that the religion can get in the way of Arvo's music. It's as if he has to set this number of word , because that is what the words are; and for a moment the music stops breathing. Instrumental pieces like Tabula rasa and Frartres are at least as moving, in a spiritual sense, as the works setting religious texts. The Passio is a great piece, but only if you get to the end where it goes into the major after this endless hour or so of the same minor chord. It wouldn't be as worthwhile without that hour, but getting there is hard work.'

Passio crystallizes one of the composer's most celebrated sayings: 'It is enough to play a single note beautifully.' I ask Pärt to expand on the point. 'If that happens then there's nothing to say about it. It can't be described. This is the mystery of music . It may sound a bit metaphorical. It's an inner attitude of the composer: your whole being must be prepared for it. I'm talking of an inner tone. You could perhaps compare it with the up-beat of a conductor. There is no music yet. We don't hear a thing, but the musicians can see it. They know character, dynamic, tempo: everything is there. This is the one tone.'

It's a long journey from what Pärt has called 'the sterile democracy' of 12-tone music, to the tintinnabulation of this 'one tone'. Yet the conductor Dennis Russell Davies makes what may seem a surprising connection. 'Arvo can write a piece lasting seven or eight minutes, that is a world unto itself, and quite exhausting to listen to if you listen intensively. In that respect, and in the way the small episodes are important to achieving the overall structure, a work like Festina lente has a strong similarity to certain structures in Webern, although the piece doesn't sound like Webern in any way. You need to understand what the overall shape of the piece is, then what the individual voices in a measure or two do. They have a life of their own: it's very difficult to achieve the fluidity that makes all these things apparent to the listener. To begin with, the architecture seems quite transparent , but the more time you spend with the music, and the more time you spend with him, the more you learn that what is notated is just the bare bones. For Arvo, the music is not ever finished.'

And yet each performance in itself must be achieved as fully as possible. The composer himself speaks eloquently of the tortuous experience of hearing a new work performed. 'There are two things happening simultaneously . Everything is known to me, and at the same time everything is unknown and new, and these two forces sometimes fight with each other. You have to be lucky when you hear a work for the first time. Performers not used to playing my music may think that the score looks simple, but you can't simply grasp it with your bare hands. You have to have good musicians who are conscious that they are really giving birth to music, who invest as much in the music as I do when composing it. Striving for special effects doesn't work, you really have to want to get to the inner core of the music, to discover something new for yourself. Sometimes a new piece doesn't sound right at the first performance. Then I think I've made a mistake, but sometimes it's to do with the performers. Obviously both sides have to be correct. You're always at the edge of the unknown, and that's precisely what is so fascinating.'

When a performance of Pärt's music comes off, the listener too may feel at the edge of the unknown, in some timeless zone where everything is about to begin. That sense of the slate having been cleared gives one of Pärt's most famous pieces its title, an expression he uses to describe the process of composition: 'When I begin a new work, I have to start from scratch again, from nothing. I have to be cleared of everything: Tabula rasa.'

This article originally appeared in the September 1996 issue of Gramophone. To enjoy exclusive interviews with classical music artists and composers every month, subscribe to Gramophone: magsubscriptions.com