A major new star-studded studio opera recording? That's worth celebrating

Martin Cullingford, Gramophone Editor

Monday, January 30, 2023

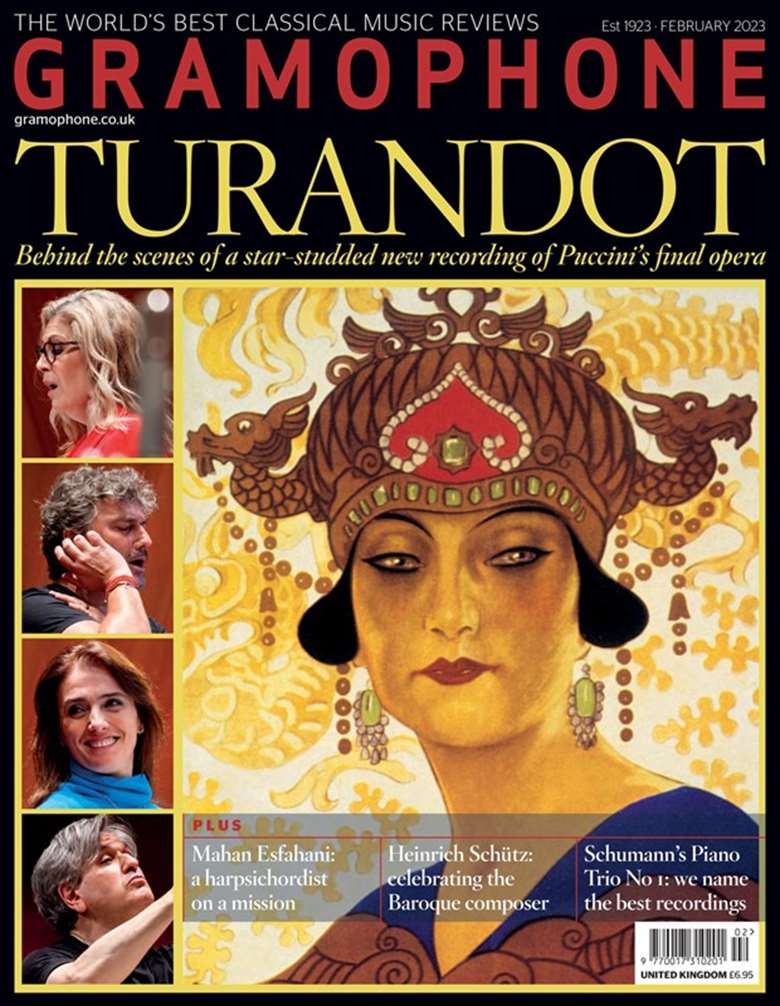

Gramophone goes behind the scenes as Sir Antonio Pappano and his hand-picked soloists record Turandot

Step back a few decades and studio recordings of operas featuring the day’s biggest stars were frequent flagship projects for many major labels. Sometimes they’d preserve a production from an opera house, but more often they were purely bespoke, capturing collaborations that were never heard on stage, or even artists in roles they’d never perform live. There was, of course, more money in recording back then, an era in which demand for physical products, LP and then CD, was substantial. It’s different today. There’s still a happily healthy flow of studio recordings of solo and chamber music, orchestral works too – but opera is different.

That’s why a recording of Turandot, conducted by arguably today’s leading Puccinian, Sir Antonio Pappano, and starring singers at the summit of their profession – Jonas Kaufmann as Calaf, Sondra Radvanovsky as Princess Turandot, Ermonela Jaho as Liù (the only cast member to have sung her role before) and Michael Spyres (who would be unlikely these days to be heard live in the small role of Altoum) – is worthy of in-depth exploration and celebration.

It’s not just a wonderful thing for us listeners – the artists too have clearly relished the experience. ‘I never want to learn another role in any other way except by recording it,’ Radvanovsky tells the article’s author Neil Fisher. That’s not a luxury she’ll be able to enjoy too often sadly, though ironically the opportunity to have done so comes from the same label – albeit after a name change – that was, back in 2005, declared to have released the final great studio opera recording, a Tristan und Isolde featuring Plácido Domingo and Nina Stemme, again conducted by Pappano. Happily, the prediction proved wrong, with the label – today Warner Classics – following it with other such recordings including, a decade later, a studio Aida.

But if it all feels like a joyful step back in time, let’s not discount the developments our own day has brought. Our Online Concerts and Events page is full of online opera broadcasts, while brilliant opera DVDs continue to enrich the catalogue, many owing their origins to the commitment by venues to streaming their productions. Meanwhile, studio recordings of lesser-known operas, often tied in with concert performances, from the likes of Opera Rara or Palazzetto Bru Zane, allow us to hear works that even the bravest venue is unlikely to risk staging.

I write at a depressing time for opera here in the UK. Both Glyndebourne and Welsh National Opera have announced that Arts Council cuts have forced them, in turn, to cut their touring work, denying many towns and cities the visits that an earlier generation will have enjoyed. The exact nature of English National Opera’s future, meanwhile, still remains worryingly uncertain. Studio recordings will never replace live performances – but they’re not meant to. Projects such as the new studio Turandot are part of the wider way audiences and artists alike explore and experience opera, not least in allowing us to hear the works in extraordinary sound. But they’re also a powerful reminder that today’s standards of singing and playing really are as high as they have ever been, and that we should all continue to speak out against anything that might endanger that.

This editorial appears in the new February edition of Gramophone - find out more