Leonardo da Vinci and music

Gramophone

Tuesday, April 23, 2019

I Fagiolini's Robert Hollingworth and Leonardo scholar Martin Kemp introduce their project 'Leonardo: Shaping the Invisible'

I Fagiolini and their music director Robert Hollingworth are celebrating the 500th anniversary of the death of Leonardo da Vinci this year with a new touring and recording project called 'Leonardo: Shaping the Invisible' in collaboration with Leonardo expert Professor Martin Kemp.

The project explores the connections between Leonardo's work and music by composers as diverse as Tallis, Monteverdi, Bach and Howells. The album 'Leonardo: Shaping the Invisible' will be released by Coro on April 26.

Below, Robert Hollingworth and Martin Kemp introduce a few of Leonardo's most iconic works and the music they resonate with.

Salvator mundi

WITH

Thomas Tallis – Salvator Mundi (1575)

Herbert Howells – Salvator Mundi (1936)

THE IMAGE by Martin Kemp

Leonardo’s painting – all $450 million of it – is at once the most conventional and original of his paintings. The stock frontal image of Christ blessing and holding a globe was derived from the traditional portrayal of God the Father as a stern judge. Even Leonardo could not depart from the hierarchical presentation if the image was to function. But he has worked his inventive magic with it. The globe presenting the earth (mundus) had been transformed into an orb of rock crystal, which means that Christ is holding the crystalline sphere of the fixed stars, outside which is the ineffable realm of God. Christ has become the ‘saviour of the cosmos’. The evocation of the ineffable – ultimately inaccessible to our finite understanding – is underlined by the elusiveness of Christ’s blurred features, set off against the sharper characterisation of his blessing hand. He is inviting us to think that we can see Christ but visual certainty eludes us. The painting is Leonardo’s most profound statement about the sublime otherness of the spiritual.

The title 'Salvator mundi’ was not given to paintings at this time, which were accorded various names in inventories. It was later adopted in art as the standard name from the hymn that was sung over the Christmas period.

Robert Hollingworth:

“An easy one to start: image and motets (both Howells' and Tallis') sharing the (modern) title of the painting.”

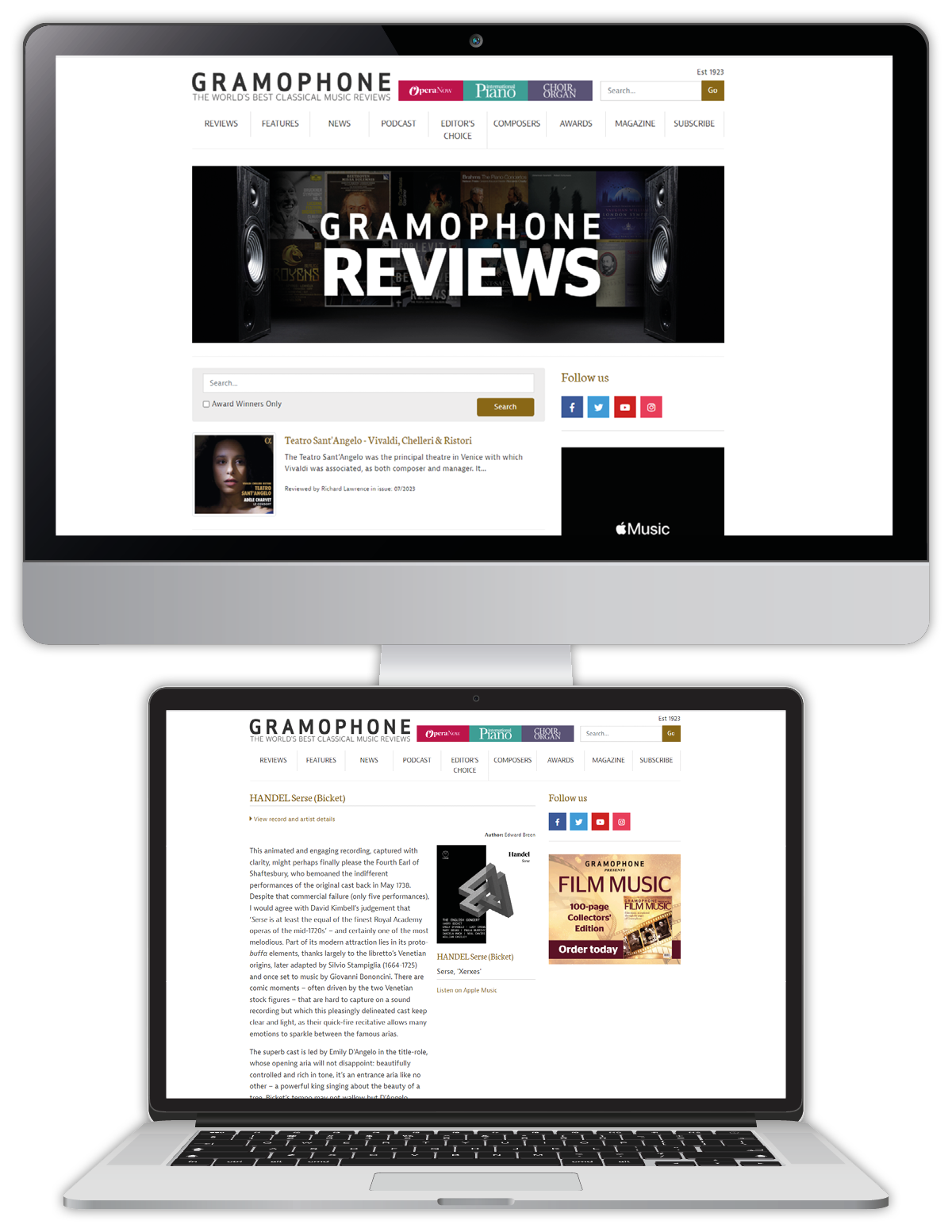

Mona Lisa

WITH

Claudio Monteverdi – Era l’anima mia (1605)

THE IMAGE by Martin Kemp

This most famed of paintings started out in 1503 as the portrait of a bourgeois Florentine woman, Lisa Gheradini, wife of the silk merchant and sharp operator, Francesco del Giocondo. Over the long period of its gestation it evolved into a ‘universal picture’ into which Leonardo poured his knowledge as a painter. It became a demonstration of the relationship of the body of the woman and the ‘body of the earth’ (with its ‘vene d’acqua’, ‘veins of water’), both living and changeable. It expresses his optical researches into light, shade and colour, and into the progressive blurring of forms. It manifests his concept of the eye as ‘window of the soul’, which allows us to take in the glories of the visible world, and transmits the sitter’s ‘concetto dell’anima’ (the ‘intention of the soul’) to the viewer.

For a woman to look at the spectator is unusual in portraiture at this time, and to smile is even more radical. The motifs of the beguiling eyes and bewitching lips of the beloved lady consciously emulate the love poetry of Dante, Petrarch and their successors (including Guarini). The divine lady’s eyes and sweet smile inflame our desperate love but she remains eternally beyond the reach of our earthly desires.

Robert Hollingworth:

To paint a female subject looking straight at the viewer and smiling was unique at the time: Leonardo spent an enormous amount of sustained effort on this image in the later part of his career, pouring his experience into it in the same way that Monteverdi did to his late a cappella madrigals. His ‘Era l’anima mia’ is at times so distilled as to be little more than declamation but…

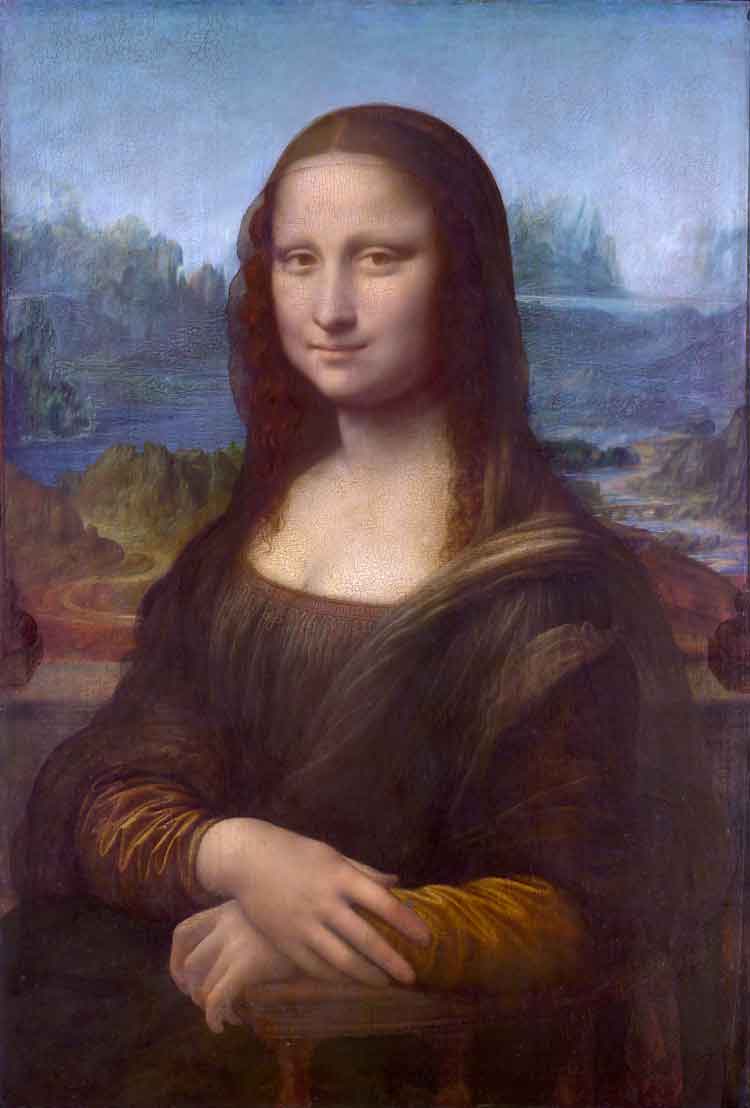

The Last Supper

WITH

Tomás Luis de Victoria – Unus ex discipulis meis (1585)

Edmund Rubbra – Amicus meus (1962)

THE IMAGE by Martin Kemp

In the ‘upper room’ of St Mark’s gospel, the various disciples react with astonishment, disbelief, anger, horror, fear, anxiety and guilt at Jesus’s calm proclamation of two of the most momentous events in the Christian story: his forthcoming betrayal and the Institution of the Eucharist (the naming of the bread as his body and the wine as his blood, as narrated by St Luke). We know from his drawings that Leonardo had considered other moments in the narrative. One sketch shows Judas rising from his traditional seat on the near side of the table to dip his bread into the same bowl as Christ, as a signal of who was to betray him. In the finished mural, the left hand of Judas hovers over a roll of bread, echoing Christ’s right hand.

This is just one of several allusions to other moments in the story of Christ and the disciples. The characteristically belligerent St Peter holds the knife with which he is to cut off the ear of a soldier at Christ’s arrest, after Judas has kissed his master to identify him. The knife points to St Bartholomew at the end of the table who is to be martyred by flaying. StThomas raises the finger with which he intends to verify the wound in Christ’s side after the Resurrection, also signalling the heavenly realm above.

Each disciple reacts individually according to what Leonardo called ‘il concetto dell’anima’ ('the intention of the soul'). He had researched the way that the brain and its neurological plumbing took in sensory information (such as Christ’s terrible pronouncement) and transmitted impulses of motion and emotion to the face, body and limbs.

As always with Leonardo his science works in partnership with his creative fantasia in service of meaning.

Robert Hollingworth:

Disciples react with astonishment, disbelief, anger, horror, fear and guilt at Jesus’s calm proclamation of his betrayal and the Institution of the Eucharist. Our two pieces are reflections from the Holy Week service of Tenebrae: an apparently simple but peerless setting by Victoria and a powerfully dramatic one by Edmund Rubbra.

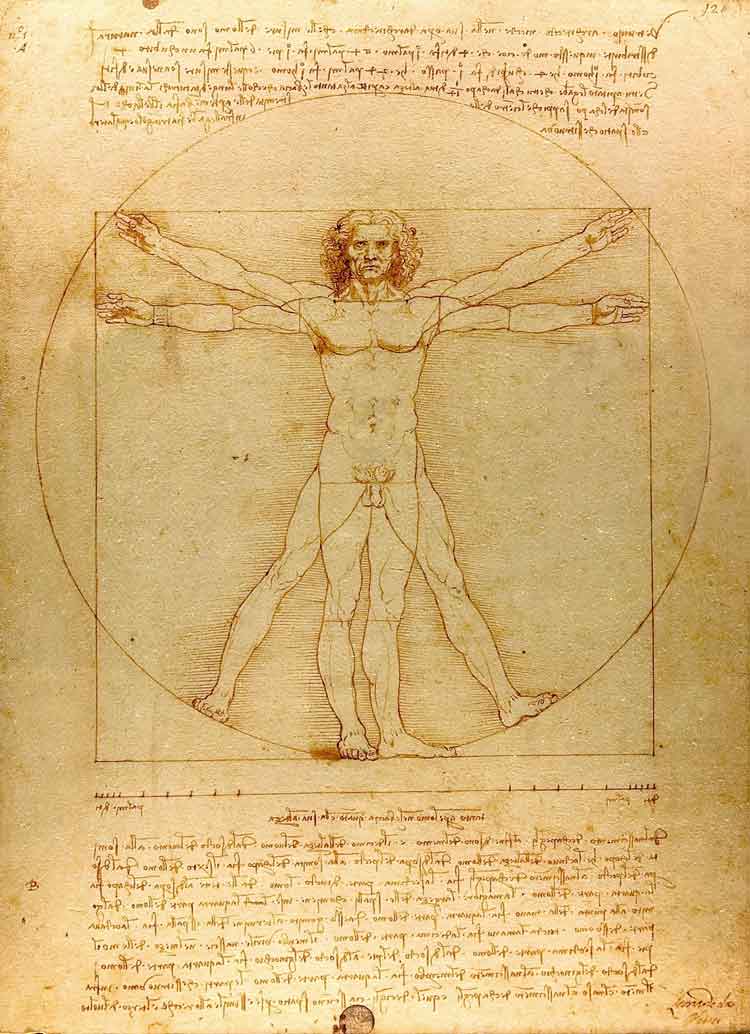

The ‘Vitruvian Man’

WITH

JS Bach – Art of Fugue No 1 (c1740-50)

THE IMAGE by Martin Kemp

Leonardo tells us that this most famous of drawings is based on a statement in the Ten Books of Architecture by the ancient Roman architect, Marus Vitruvius Pollio:

If a man lies on his back with hands and feet outspread, and the centre of a circle is placed on his navel, his figure and toes will be touched by the circumference. Also....a square can be discovered as described by the figure. For if we measure from the sole of the foot to the top of the head, and apply the measure to the outstretched hands, the breadth will be found equal to the height.

Unsurprisingly a number of draftsmen had tried to illustrate Vitruvius’s formula, but they assumed that the circle and square should both be centered on the navel, which is not what Vitruvius actually said. The only convincing way to make the formula work is to assume that that the square is centered on the man’s genitals. Leonardo additionally shows that ‘If you open your legs so much as to decrease your height by 1/14 and spread and raise your arms so that your middle finger are on a level with the top of your head, you must know that the navel will be the center of a circle of which the outspread limbs touch the circumference; and the space between the legs will form an equilateral triangle’. Leonardo’s positioning of he fingers and toes is the only arrangement that works with the main circle.

The overall schema is geometrical, but the internal proportions are numerical. For example, ‘the face from the chin to the top of the forehead and the roots of the hair is a tenth part [of the body]; also the palm of the hand from the wrist to the top of the middle finger is as much; the head from the chin to the crown, an eighth part’. The many compass marks show that the internal music of the body is composed from measured intervals, not pentagons or the other geometrical figures that are often imposed on the image. The numerology is analogous to Pythagorean intervals in music.

Leonardo saw the proportional harmonies of human body and the proportional harmonies of music as originating from the fundamentals of God’s design. The proportional diminution of forms in linear perspective and the proportional diminution of ‘impetus’ in a moving body manifested the same rule of divine mathematics.

Robert Hollingworth:

Leonardo's drawing is his solution to the Roman architect Marcus Vitruvius Pollo's conundrum about geometrical and arithmetic proportions in the human body. It wasn't hard to associate this with Bach, whose balance of form and proportion is nowhere better shown than in the Art of Fugue.

The Battle of Anghiari

WITH

Clément Janequin's 'La Guerre'

THE MUSIC by Robert Hollingworth

Leonardo's graphic scene of the 'bestial' passions of battle commemorated a Florentine victory against the Milanese, whereas Clément Janequin's slightly Pythonesque 'La Guerre' from 1528 lauds a French victory against the Milanese, complete with written-in sound effects for exploding cannons, arrow flight, horses hooves and the screams of the fleeing Swiss mercenaries ("Run away...").

For further information and tour dates, please visit http://leonardo.ifagiolini.com/